-

1 Scope and Structure of the Article

Since 1 July 2021, the VAT e-commerce rules apply in the European Union (EU). In a nutshell, these rules mean that e-commerce transactions (mostly online sales to consumers) are taxed in the Member State of the consumer (i.e. the Member State of consumption). In principle, an entrepreneur must register in each Member State of consumption in order to declare and remit the VAT due there. However, the VAT e-commerce rules have brought about an administrative simplification for entrepreneurs by expanding the scope of the existing Mini-One-Stop-Shop (MOSS) system, reserved for cross-border trade in telecommunications, broadcasting and electronic (TBE) services, to include e-commerce. Hence, the MOSS became the One-Stop-Shop (OSS). Under this system, an entrepreneur must declare and remit VAT on e-commerce transactions in one Member State (i.e. the Member State of identification). Subsequently, the Member State of identification transmits the declaration and the payments to the Member State of consumption.

Making sure that the VAT due is paid and collected in the correct jurisdiction in this globalised and digitalised world where consumers can easily buy products across borders appears to be a great challenge for the EU tax administrations.1x A. Sutton, ‘Administrative Law Training: EU Tax Law EU VAT – Problems and Challenges’, European Judicial Training Network (EJTN), at 6 (8 March 2021). It is essential for the proper functioning of the VAT e-commerce rules that the Member States’ tax administrations (hereinafter: the Member States) cooperate with each other. Furthermore, the obligations regarding administrative cooperation of each Member State must be clearly defined. However, it is also essential that the Member States actively use the administrative cooperation mechanisms made available by the European Commission (i.e. that the rules are also practically implemented). The rules on administrative cooperation are laid down in Council Regulation 904/20102x Council Regulation 904/2010 of 7 October 2010 on administrative cooperation and combating fraud in the field of value added tax, OJ L 268, 12 October 2010, at 1-18. (the Regulation on administrative cooperation). Close cooperation between the Member States is vital now that VAT on e-commerce transactions is due in the Member State of consumption while the VAT is reported in another Member State, i.e. the Member State of identification in case the OSS is used.3x G. Beretta, ‘VAT and Administrative Cooperation in the EU’, 100 Tax Notes International 71, at 72 (2020). When collecting the VAT due, Member States should not only monitor the correct application of the VAT due in their territory but also assist other Member States to ensure the correct application of VAT due in another Member State in relation to an activity carried out on or reported in their territory.4x Art. 1 and preamble 7 Council Regulation 904/2010. In this respect, monitoring cross-border transactions by the Member State of consumption depends on information. However, this information is often in possession of the Member State of establishment of the taxpayer or can, in any case, more easily be obtained by that Member State.5x Preamble 8 Council Regulation 904/2010. It is, therefore, important that the Member States collect information and exchange it with each other.

Although progress has been made concerning the administrative cooperation between the Member States through the years,6x E.g.: (1) European Commission, Proposal to Amend Regulation 904/2010 to Strengthen Administrative Cooperation on VAT, COM(2017) 706 final; (2) European Commission, Proposal for a Council Directive Harmonising and Simplifying Certain VAT Rules and Introducing the Definitive System for the Taxation of Trade Between the Member States, COM(2017) 569 final; and (3) Council Directives 2017/2455 and 2019/1995. and the past has shown that the Member States are able and willing to cooperate7x ‘In light of the end of bank secrecy, the implementation of the common global standard on automatic exchange of information, not to mention within the EU, the extension of automatic exchange of information to almost all categories of income (EU Administrative Cooperation Directive: Council Directive 2011/16/EU of 15 February 2011 on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation and repealing Directive 77/ 799/EEC, OJ L64/1 (11 March 2011), Art. 8)’. E. Traversa, ‘Ongoing Tax Reforms at the EU Level: Why Trust Matters’, 47(3) Intertax 244, at 245 and footnote 4 (2019). and to overcome political differences between them,8x ‘The Member States were able to overcome their political differences and agreement was reached on many files on 2 October 2018. On that day, consensus was reached in the ECOFIN meeting on the quick fixes, one of the main subjects of our previous article. On top of that, the directive to allow Member States to align the VAT rates they set for e-publications, currently taxed at the standard rate in most Member States, with the more favourable regime currently in force for traditional printed publications was approved, and, last but not least, the new rules to exchange more information and boost cooperation on criminal VAT fraud between national tax authorities and law enforcement authorities were formally adopted as well on the same day.’ M.M.W.D. Merkx and J. Gruson, ‘Definitive VAT Regime: Ready for the Next Step?’, 3 EC Tax Review 136, at 136 (2019). some scholars think that putting the collection of VAT that accrues to one Member State in the hands of another Member State is a bridge too far.9x Merkx and Gruson, above n. 8, at 149. With the introduction of the MOSS system, the collection of VAT that accrued to the Member State of consumption had already been partially transferred to the Member State of identification. With the OSS system, this has been extended. The European Commission wants to extend the OSS system further and further.10x As the definitive VAT regime continues to be delayed, the European Commission is pushing for extended cooperation through enhanced information exchange and the OSS system. Research shows that this potential policy option can help reduce the VAT Gap and reduce businesses’ compliance costs. In this context, the author of this article notes that the (functioning of the) OSS system can contribute to this to some extent. However, the proper functioning of the OSS system relies on effective administrative cooperation between the Member States. The latter does not seem to be sufficiently taken into account by the European Commission, as discussed in Section 7 of this article. M. Mercedes Garcia Munoz and J. Saulnier, Fair and Simpler Taxation Supporting the Recovery Strategy: Ways to Improve Exchange of Information and Compliance to Reduce the VAT Gap: European Added Value Assessment (2021). However, it appears that administrative cooperation is lacking and that not all the Member States are willing to cooperate.11x E.g.: Bundesrechnungshof, Spring Report 2014 on Federal Financial Management in 2013 (2014); National Audit Office of Lithuania, Electronic Commerce Control – Executive Summary of the Public Audit Report, No. VA-P-60-12-7 (2015), at 1-6; European Commission and Deloitte, VAT Aspects of Cross-border E-commerce: Options for Modernisation: Final Report. Lot 1, Economic Analysis of VAT Aspects of E-commerce (2015), at 1-205; European Commission and Deloitte, VAT Aspects of Cross-border E-commerce: Options for Modernisation: Final Report. Lot 2, Analysis of Costs, Benefits, Opportunities and Risks in Respect of the Options for the Modernisation of the VAT Aspects of Cross-border E-commerce (2016a), at 1-320; European Commission and Deloitte, VAT Aspects of Cross-border E-commerce: Options for Modernisation: Final Report. Lot 3, Assessment of the Implementation of the 2015 Place of Supply Rules and the Mini-One Stop Shop (2016b), at 1-270; Netherlands Court of Audit, VAT on Cross-Border Digital Services – Enforcement by the Netherlands Tax and Customs Administration (2018), at 1-56; European Court of Auditors, E-commerce: Many of the Challenges of Collecting VAT and Customs Duties Remain to be Resolved, No. 12 (2019), at 1-66. See also: M.M.W.D. Merkx, The Wizard of OSS: Effective Collection of VAT in Cross-border E-commerce (2020), at 29. This can endanger the proper functioning of the VAT system now that the administrative cooperation mechanisms depend on the active participation of the Member States. An important factor in this lack of cooperation is the lack of trust between the Member States. The importance of cooperation and trust between the Member States for a properly functioning VAT system in a global and digitalised economy is recognised by the European Commission.12x European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on an action plan on VAT Towards a Single EU VAT Area – Time to Decide, COM(2016) 148 final (2016), at 1-14; European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council – An Action Plan for Fair and Simple Taxation Supporting the Recovery Strategy, COM(2020) 312 final (2020), at 1-17. However, the impact of a lack of trust between the Member States on the cooperation between them and, therefore, on the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules is insufficiently discussed in the literature and is not adequately addressed by either the Member States or the European Commission.1.1 Scope of the Article

This article is a preliminary analysis and explores, from a theoretical perspective, the role of trust in regulatory interorganisational relations (i.e. the relations between the Member States) and how the trust-building process between the Member States can be positively influenced to enhance the practical implementation of the Regulation on administrative cooperation regarding VAT e-commerce. In this regard, the article starts in Section 2 by describing the methodological approach. The VAT e-commerce rules and the rules on administrative cooperation (as laid down in the Regulation on administrative cooperation) are described in Sections 3 and 4, respectively, to provide a better understanding of the VAT e-commerce context in question. Thereupon, Section 5 broadens out by describing, from a theoretical perspective, the role of trust in regulatory interorganisational relations (e.g. the relation between the Member States) and how trust can be positively influenced. Subsequently, it is important to assess in Section 6 how the VAT e-commerce rules are implemented in practice by the Member States and whether a lack of trust between them is perceived. As will appear in this section, a lack of trust is perceived. In this manner, the theoretical lessons of Section 5 and its implications might help in enhancing the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules as described in Sections 3 and 4. The lack of trust between the Member States is worrying and needs to be tackled. In the first place, this needs to be done by the Member States. However, as will appear in Section 6, the Member States have little incentive to change their current practice. Therefore, the European Commission must take action because the European Commission must monitor the practical implementation of EU law by the Member States. In this regard, Section 7 explores whether the lack of trust is sufficiently addressed by the European Commission. It will appear from this section that the European Commission does not adequately address the lack of trust between the Member States. Therefore, Section 8 discusses, based on the preceding conclusions, how the trust-building process between the Member States can be improved to enhance the practical implementation of the Regulation on administrative cooperation and what this means within the VAT e-commerce context. This article ends with a conclusion in Section 9.

-

2 Relevance and Methodological Approach: Applying Trust Literature to the VAT E-commerce Context

The aim of this article is to explore the role of trust between the Member States and its impact on the practical implementation of the Regulation on administrative cooperation regarding VAT e-commerce. The effective practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules depends on active cooperation, which requires trust, between the Member States. Research in this regard is needed because the impact of a lack of trust between the Member States on the cooperation between them and, therefore, on the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules is insufficiently discussed in the literature and is not adequately addressed by either the Member States or the European Commission. According to the European Commission, amending the Regulation on administrative cooperation will not bring any added value as the instruments for administrative cooperation themselves are appropriate.13x European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document – Impact Assessment – Accompanying the Document Amended Proposal for a Council Regulation Amending Regulation (EU) No 904/2010 as Regards Measures to Strengthen Administrative Cooperation in the Field of Value Added Tax, SWD(2017) 428 final (1-206) (2017), at 9. With ‘implementation’ the European Commission probably meant the practical implementation of Council Regulation 904/2010 because a Council Regulation applies directly to the Member States and does not have to be formally implemented (i.e. transposed) into national law. It is the practical implementation in certain Member States that needs to be addressed. This article shows how the trust literature could be useful to enhance the practical implementation by the Member States of the Regulation on administrative cooperation regarding VAT e-commerce. The implications of the trust literature for both the Member States and the European Commission will be discussed, along with the question of whether further research on this topic is necessary.14x The author is currently working on PhD research regarding what is described in this article. The research will be further explored and presented to various experts active in science or practice on this topic to further develop the framework. Furthermore, field research with interviews will also be part of the methodological approach. The results of this PhD research will contribute to more effective practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules and administrative cooperation by the Member States.

This article is based on the following methodological approach. The data used for the analysis is qualitative and descriptive. Furthermore, the data used is collected through a literature review15x H. Snyder, ‘Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines’, 104 Journal of Business Research 333, at 333 (2019). See also: R.F. Baumeister and M.R. Leary, ‘Writing Narrative Literature Reviews’, 1(3) Review of General Psychology 311 (1997); D. Tranfield, D. Denyer, & P. Smart, ‘Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review’, 14(3) British Journal of Management 207 (2003). and interpreted through an integrative review.16x ‘The integrative literature review is a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated.’ R.J. Torraco, ‘Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples’, 4(3) Human Resource Development Review 356, at 356 (2005). The results obtained are aggregated to generate a new perspective on how trust can contribute to the practical implementation of the Regulation on administrative cooperation regarding VAT e-commerce. -

3 VAT E-commerce Rules

Entrepreneurs who supply goods to private individuals in a Member State may face the VAT rules for distance sales of goods. Distance sales of goods refers to distance sales of goods imported from third territories or third countries or intra-Community distance sales of goods.17x For a definition, see: Art. 14(4) of the VAT Directive. European Commission, Explanatory Notes on VAT E-commerce Rules (September 2020), at 8. If these rules apply, the supplier owes VAT in the Member State of arrival of the goods instead of the country of departure of the goods.18x The place of supply of intra-Community distance sales of goods is determined in Art. 33(a) of the VAT Directive (i.e. Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 on the common system of value added tax, OJ L 347, 11 December 2006, at 1-118; hereinafter: VAT Directive). The place of supply of distance sales of goods imported from third territories or third countries into a Member State other than that in which dispatch or transport of the goods to the consumer ends is determined in Art. 33(b) VAT Directive. Art. 33(c) VAT Directive determines the place of supply of distance sales of goods imported from third territories or third countries into the Member State in which dispatch or transport of the goods to the consumer ends. The consequence of applying the rules for distance sales of goods is that the supplier concerned must register for VAT in each Member State where he or she is required to declare distance sales of goods.19x European Commission (2020), above n. 17, at 6 and 34.

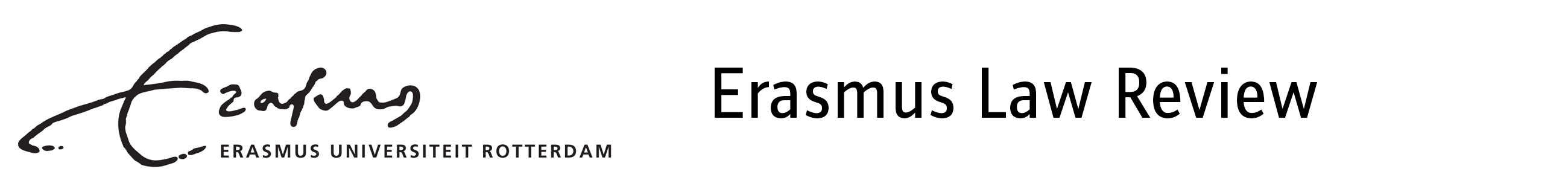

Representation of the (Import-)One-Stop-Shop system. ©

In order to avoid administrative burdens for entrepreneurs, the European Commission has provided for a simplification of the VAT declaration process by establishing the Import-OSS (IOSS) and OSS system. The IOSS system has been established for distance sales of goods coming from third countries or territories with an intrinsic value of €150 or less.20x Art. 369l VAT Directive. The OSS system has been established for intra-Community distance sales of goods and for all services provided to a consumer in a Member State (other than that in which the supplier is established).21x European Commission (2020), above n. 17, at 33 and 34. The OSS system has two schemes: the non-Union scheme (Arts. 358a-369 VAT Directive; Arts. 57a-63c VAT Implementing Regulation) and the Union scheme (Arts. 369a-369k VAT Directive; Arts. 57a-63c VAT Implementing Regulation). For more information on the practicalities, see: European Commission, Guide to the VAT One Stop Shop (March 2021). The OSS system does not change the place of supply rules. Hence, the general rule for B2C services is the place where the supplier is established. However, some specific B2C services are taxable in another Member State (e.g. TBE services, accommodation, transport, services related to immovable property, restaurant and catering services for consumption on board of ships, aircraft or trains), for which the OSS system can also be used.

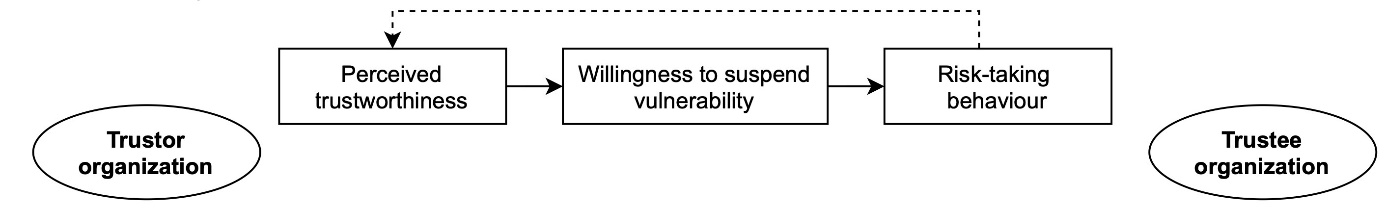

Under these systems, the VAT declaration process is simplified because instead of having to register and file a VAT declaration in the Member State where the supply is taxed (i.e. the Member State of consumption), the entrepreneur can choose to file a VAT declaration in one Member State (i.e. the Member State of identification22x Art. 358a(2) VAT Directive (non-Union scheme); Art. 369a(2) VAT Directive (Union scheme); European Commission (2020), above n. 17, at 33. Art. 369l(3) VAT Directive (Import scheme) jo. Art. 369s VAT Directive.). This Member State will then forward the VAT declaration and the related payment to the Member State where the VAT is due. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

In the case of sales of goods from outside the EU, there are two taxable events for VAT purposes: the distance sale of imported goods from a third country or third territory to an EU consumer and the importation of goods in the EU.23x European Commission (2020), above n. 17, at 52. The VAT consequences for both the import and the distance sale depend on whether use is made of the IOSS. When a supplier applies the IOSS, the import will be exempt from VAT.24x Art. 143(1)(ca) VAT Directive. However, VAT is due on the distance sales of goods in the Member State of arrival, which can be declared through an IOSS declaration. If the IOSS does not apply, the import will be subject to VAT in the Member State of destination where the goods are released for free circulation.25x Art. 60 VAT Directive. The special arrangement, also known as the postal and courier arrangement, may be applied here but only when the imported goods have an intrinsic value of €150 or less and the imported goods remain in the Member State of importation.26x Art. 369y VAT Directive. Postal and courier companies collect the VAT due at import from the consignee and pay it to the customs authorities by submitting monthly electronic declarations.27x Arts. 369z and 369zb VAT Directive. The special arrangement is beyond the scope of this article.

What is unique about the (I)OSS system, in contrast to other forms of international trade (e.g. intra-Community acquisitions of goods, A-B-C supply chain transactions, call-off stock arrangements, internationally provided B2B services), is that the Member States of consumption relinquishes the task of VAT collection to the Member State of identification. In addition to the well-known exchanges of information, VAT declarations and corresponding payments must now also be communicated between the Member States.3.1 The Involvement of Third Parties

To help the Member States, the European Commission decided to involve some third parties (i.e. certain platforms and payment service providers) in the VAT reporting or collection on e-commerce transactions.

First, platforms occupy a special position in the application of the VAT e-commerce rules because they bring suppliers and consumers into contact through their website or marketplace. A deeming provision applies,28x For a broader description of the deeming provision of Art. 14a VAT Directive, see M. Lamensch, M. Merkx, J. Lock, & A. Janssen, ‘New EU VAT-related Obligations for E-commerce Platforms Worldwide: A Qualitative Impact Assessment’, 13(3) World Tax Journal 441, at para. 3 (2021). which stipulates that in certain situations, platforms are deemed to supply the goods to the consumer instead of the actual supplier.29x For more information see European Commission (2020), above n. 17, sec. 2.1 at 11-26. For the deeming provision to apply, it is required that the platform facilitates the sale between the supplier and the consumer.30x The concept of facilitation is clarified in Art. 5b VAT Implementing Regulation. For more information see European Commission (2020), above n. 17, secs. 2.1.6-2.1.8 at 17-22. When a platform facilitates and falls under the deeming provision, this provision applies in the following two situations: when a platform facilitates distance sales of goods from third countries or third territories with an intrinsic value not exceeding €150, regardless of where the supplier is established,31x Art. 14a(1) VAT Directive. and when a platform facilitates intra-Community distance sales of goods and local supplies to consumers by suppliers established outside the EU.32x Art. 14a(2) VAT Directive. The consequence of applying the deeming provision in these two situations is that the platform is responsible33x For a broader description of joint and several liability models, see: A. Janssen, ‘The Problematic Combination of EU Harmonized and Domestic Legislation Regarding VAT Platform Liability’, 32(5) International VAT Monitor 231 (2021); Lamensch et al., above n. 28. Some Member States adopted joint and several liability rules for platforms, and no indication exists that these rules will be rescinded as of 1 July 2021. These authors state that extra burdens arise from the combination of harmonised and domestic legislation if all Member States introduce their own domestic liability rules because the legal framework will become even more unbearable for platforms. for declaring and paying the VAT that becomes due at the moment the payment is accepted.34x Art. 66a VAT Directive jo. Art. 41a VAT Implementing Regulation. A special record-keeping obligation also applies to platforms that facilitate the supply of goods to consumers in the EU.35x Art. 54c(1) VAT Implementing Regulation. This article ‘clarifies that the deemed supplier shall keep the following records: 1. If he uses one of the special schemes provided for in Chapter 6 of Title XII of the VAT Directive: the records as set out in Article 63c of the VAT Implementing Regulation…; 2. If he does not use any of these special schemes: the records as set out in Article 242 of the VAT Directive. In this situation, each national legislation sets out what are the records to be kept by taxable persons and in which form they should be kept.’ European Commission (2020), above n. 17, at 27. The precise obligations36x For a broader impact assessment, see Lamensch et al., above n. 28, paras. 4 and 5. And for more information on the various business models of platforms, see Lamensch et al., above n. 28, para. 2. depend on the situation in which the platform concerned finds itself.37x As of 1 January 2023, platforms will also have to deal with a set of information obligations under the new DAC7 Directive (Council Directive (EU) 2021/514). The DAC7 Directive does not fall within the scope of this article. For more information, see M. Merkx, A. Janssen, & M. Leenders, ‘Platforms, a Convenient Source of Information Under DAC7 and the VAT Directive: A Proposal for More Alignment and Efficiency’, 4 EC Tax Review 202 (2022).

Second, as of 1 January 2024, payment service providers (PSPs) will also be involved as third parties in the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules.38x Council Directive 2020/284 of 18 February 2020 amending Directive 2006/112/EC as regards introducing certain requirements for payment service providers, OJ L 62, 2 March 2020, at 7-12 and Council Regulation 2020/283 of 18 February 2020 amending Regulation (EU) No 904/2010 as regards measures to strengthen administrative cooperation in order to combat VAT fraud, OJ L 62, 2 March 2020, at 1-6. The PSP rules stipulate that certain PSPs39x PSPs include credit institutions, electronic money institutions, post office giro institutions and payment institutions or legal and natural persons who have been granted an exemption to provide certain payment services. These natural or legal persons benefit from an exemption in accordance with Art. 32 Council Directive 2015/2366. PSPs located outside the EU do not fall within the scope of the PSP rules. Art. 243a Council Directive 2020/284 and Art. 1(1)(a-d) Council Directive 2015/2366. Council Directive 2020/284, preamble paras. 4 and 9. should collect and transmit certain VAT-relevant payment data40x See Art. 243d(1)(2) Council Directive 2020/284. regarding cross-border payments41x Council Directive 2020/284, preamble para. 6. The payee (i.e. the intended recipient) of the payment must be located in a third country or territory or in a Member State other than that of the payer, according to Art. 243b(1) Council Directive 2020/284. to the Member States.42x For more information on the PSPs rules, see: M.M.W.D. Merkx and A.D.M. Janssen, ‘A New Weapon in the Fight against E-commerce VAT Fraud: Information from Payment Service Providers’, 30(6) International VAT Monitor 231 (2019); M.E. van Hilten and G. Beretta, ‘European Union – The New VAT Record Keeping and Reporting Obligations for Payment Service Providers’, 31(4) International VAT Monitor 169 (2020). The aim of these rules is to combat VAT fraud. Tax administrations are often unable to determine the identity of fraudulent companies hiding behind a domain name, their turnover and location. Private consumers do not have to keep accounts, and the Member State of consumption does not have appropriate tools to detect and control these fraudulent companies.43x Council Directive 2020/284, preamble para. 2. PSPs, to the contrary, hold information, which may enable the Member States to monitor e-commerce transactions and to detect fraudulent businesses.44x Ibid., preamble paras. 3 and 5. The retained information must be made available by the PSP to the PSP’s home Member State. However, if the PSP provides payment services in a Member State other than the home Member State, the information should be made available to the host Member State.45x Art. 243b(4)(b) Council Directive 2020/284. Those Member States shall collect and store at the national level the information made available.46x Art. 24b(1)(2) Council Regulation 2020/283. Subsequently, Member States shall transmit the stored information via a central electronic system called CESOP. The data stored in CESOP is then aggregated, analysed and made accessible47x Art. 24c(1) Council Regulation 2020/283. (see Section 4 for more information on CESOP).

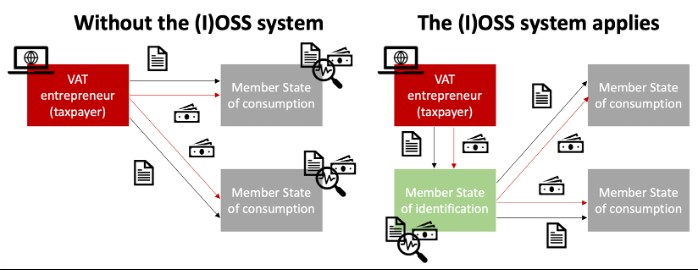

In order for the VAT e-commerce rules and, more specifically, the OSS system and the exchange of information obtained from third parties to function properly, cooperation between the Member States is important. How this cooperation is legally structured is discussed in the next section.An overview of the administrative cooperation rules, mechanisms and networks in the field of VAT.48x This figure is based on European Commission (2017), above n. 13, at 6.

-

4 Rules on Administrative Cooperation

The rules on administrative cooperation in the field of VAT are laid down in the Regulation on administrative cooperation. This Regulation provides for various rules, networks and mechanisms to promote and facilitate administrative cooperation between the Member States. The Regulation on administrative cooperation, e.g., contains provisions regarding:

The exchange of information49x The exchange of information between the Member States is on request, automatic or spontaneous (Arts. 7, 13, 14 and 16 Council Regulation 904/2010). The Member States must store the information required (Art. 17 Council Regulation 904/2010) in a national electronic system in which access to the other Member States to the information is to be granted (Arts. 18 and 21 Council Regulation 904/2010). The Member States have the obligation to ensure the accuracy, completeness and actuality of the electronically stored information (Arts. 19 and 22 Council Regulation 904/2010). Subsequently, the Member States can use the CCN/CSI network or any other similar secure network for the information exchanges. Art. 24 Council Regulation 904/2010. According to Art. 2(1)(q) Council Regulation 904/2010, the CCN/CSI network is a ‘… common platform based on the common communication network (hereinafter the “CCN”) and common system interface (hereinafter the “CSI”), developed by the Union to ensure all transmissions by electronic means between competent authorities in the area of customs and taxation’. between the Member States and with the European Commission or other EU bodies.50x E.g., Europol. Art. 49 Council Regulation 904/2010.

The Eurofisc network, which is established for the swift exchange, process and analysis of information on cross-border VAT fraud and for the coordination of follow-up actions (i.e. multilateral cooperation between the Member States).51x Art. 33 Council Regulation 904/2010. The Eurofisc network is decentralised and a framework without legal personality. For more information on Eurofisc see Art. 36 Council Regulation 904/2010 or European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11, at 18. Member States can choose to participate in Eurofisc or not, but when they participate they must do so actively.52x Art. 34 Council Regulation 904/2010. E.g., all the Member States have joined the Transaction Network Analysis (also known as TNA, which is a special working field of Eurofisc and is a tool for the exchange of information and the joint processing of VAT data for Eurofisc officials) as full members except for Germany and Slovenia, who are observers. European Commission (2017), above n. 13, at 38. Besides, a TNA expert team is established to group the Member States’ resources in order to assist the European Commission in the development of the TNA software, but only the following Member States are participating: Belgium, Austria, France, Hungary, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands. The Council of the European Union, Commission Staff Working Document Fiscalis 2020 Programme Progress Report 2019, SWD(2020) 402 final (2020), at 24.

The VAT Information Exchange System (also known as VIES), which is an electronic system for the exchange of information about EU VAT registration numbers.53x For more information see: Art. 31 Council Regulation 904/2010; European Commission (2017), above n. 13; I. Butu and P. Brezeanu, ‘Fighting VAT Fraud through Administrative Tools in the European Union’, 1(22) Finance – Challenges of the Future 90 (2020).

CESOP, which is a central electronic system that the Member States use to store the information obtained from PSPs, as explained in Section 3.1.54x In CESOP, anti-fraud officials in the Member States within the Eurofisc framework can further process the information stored. For more information, see Art. 24(b)(d) Council Regulation 2020/283, European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document – Impact Assessment – Accompanying the Document Proposal for a Council Directive Amending Directive 2006/112/EC as Regards Introducing Certain Requirements for Payment Service Providers and Proposal for a Council Regulation Amending Regulation (EU) No 904/2010 as Regards Measures to Strengthen Administrative Cooperation in Order to Combat VAT Fraud, SWD(2018) 488 final (2018), at 1-121, Merkx and Janssen (2019), above n. 42. European Commission, Central Electronic System of Payment information (CESOP), https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/taxation-1/central-electronic-system-payment-information-cesop_en (last visited 25 January 2022).

Multilateral controls (MLCs). The provisions regarding MLCs regulate the presence of the officials or tax auditors of foreign Member States in another EU tax administration’s office or, e.g., taxpayer’s premises during national administrative enquiries and simultaneous controls in two or more Member States.55x Arts. 28 and 29 Council Regulation 904/2010. See also European Commission (2017), above n. 13; European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11.

These administrative cooperation mechanisms are illustrated in Figure 2. Under the (I)OSS system, the Member State of identification has a coordinating role regarding information requests and administrative enquiries and the control of transactions and taxable persons.56x Arts. 47b-g and 47h-j Council Regulation 904/2010. Cf. A.D.M. Janssen and N. Verbaan, ‘Terug naar de tekentafel met het definitieve btw-systeem’, MBB 2022-09.

4.1 Jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice on Administrative Cooperation

In enforcing the VAT e-commerce rules and collecting the VAT due, the Member States depend on each other and on their commitment to actively use the mechanisms for administrative cooperation. However, it appears from the case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) that the Member States are not obliged to cooperate beyond the mere provision of information. In the WebMindLicenses case,57x ECJ 17 December 2015, C-419/14 (WebMindLicenses Kft.), ECLI:EU:C:2015:832. The Hungarian WebMindLicenses transferred know-how to a Portuguese company via a licence agreement, which was, according to WebMindLicenses, taxable in Portugal. The Hungarian tax administration stated that the know-how transfer did not constitute a real economic transaction, that the transfer was therefore taxable in Hungary and that WebMindLicenses had committed an abuse of law, which would result in double taxation. the ECJ inferred an obligation for the Member States to request for information (to prevent double taxation) if it is essential or useful for ensuring the correct VAT application. According to De Troyer, although the ECJ, in this case, does not explicitly state that the Member States should come to an agreement regarding the VAT treatment, the ECJ started a line of reasoning for a joint effort of the Member States in the taxation of VAT through administrative cooperation.58x I. de Troyer, ‘International Cooperation to Avoid Double Taxation in the Field of VAT: Does the Court of Justice Produce a Revolution?’, 3 EC Tax Review 170, at 172 (2016). A couple of years later, the KrakVet Marek Batko case59x ECJ 18 June 2020, C-276/18 (KrakVet Marek Batko sp.k.), ECLI:EU:C:2020:485. For more information on this case, see A.D.M. Janssen, ‘International Trade, a Never-Ending Trend’, 48(12) Intertax 55 (2020). was ruled. However, the ECJ did not repeat its line of reasoning in the WebMindLicenses case and accepted, in the KrakVet Marek Batko case, double taxation by not obliging the Member States to cooperate with a view to eliminating double taxation.60x ‘… it must be stated that Regulation No 904/2010 is confined to enabling administrative cooperation for the purposes of exchanging information that may be necessary for the tax authorities of the Member States. That regulation does not therefore govern the powers of those authorities to carry out, in the light of such information, the classification of the transactions concerned under Directive 2006/112 … It follows that Regulation No 904/2010 does not lay down either an obligation requiring the tax authorities of two Member States to cooperate in order to reach a common solution as regards the treatment of a transaction for VAT purposes or a requirement that the tax authorities of one Member State be bound by the classification given to that transaction by the tax authorities of another Member State.’ Ibid., recs. 48 and 49. However, the ECJ also states that VAT collected in breach of Union law must be repaid. Ibid., rec. 52. That is, administrative cooperation is limited to the mere provision of information and the Member States do not have to cooperate to the level in which the correct VAT application is ensured. Furthermore, the Regulation on administrative cooperation does not as such confer on taxable persons any specific rights of recourse against the Member States in the event of failure to (adequately) comply with their obligations, e.g. to challenge the lawfulness of the suspension of the tax audit to which a taxpayer is subjected on the grounds of its excessive duration. This follows from the ECJ judgment61x ECJ 30 September 2021, C-186/20 (Hydina SK s.r.o.), ECLI:EU:C:2021:786. Hydina, a Slovak company, bought meat products from the Slovak company Argus Plus and deducted the VAT on that supply. The Slovak tax administration doubted whether Argus Plus had supplied the meat products and started a tax audit, which was suspended twice owing to information requests to Poland and Hungary. Eventually, the Slovak tax administration concluded that Hydina did not actually obtain meat products from Argus Plus and claimed VAT. Hydina stated that the tax audit lasted excessively long since it was not concluded within one year. in the Hydina case.62x Cf. Janssen and Verbaan, above n. 55.

The fact that Member States are not obliged to cooperate beyond the mere provision of information and that taxpayers do not obtain a right of recourse against Member States in case of non-compliance or improper compliance does not encourage the active use of administrative cooperation mechanisms by Member States. However, the effective practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules depends on active cooperation, which requires trust, between the Member States. The role of trust in the relation between the Member States and how trust is created is further described, from a broader and theoretical perspective, in the next section.Organizational trust. ©

-

5 A Theoretical Model of Organisational Behaviour and Trust

When discussing trust63x ‘Trust is a judgment based on knowledge about another party’s trustworthiness or untrustworthiness, respectively, but this knowledge is not complete. Trust implies that there is uncertainty about the trustee’s future behaviour’, F.E. Six, ‘Trust in Regulatory Relations: How New Insights from Trust Research Improve Regulation Theory’, 15(2) Public Management Review 163, at 168 (2013). ‘… trust is best defined as the intention to accept vulnerability to the actions of the other party, based upon the positive expectation that the other will perform a particular action that is important to the trustor’, F.E. Six and H. van Ees, ‘When the Going Gets Tough: Exploring Processes of Trust Building and Repair in Regulatory Relations’, in F.E. Six and K. Verhoest (eds.), Trust in Regulatory Regimes (2017), at 60-79. For a broader description of the conceptualisation of trust and distrust, see: D. Levi-Faur et al. (2020). Report on Trust in Government, Politics, Policy and Regulatory Governance: Deliverable D1.1 v.1.0. (online ed.) European Commission. between the (tax administrations of the) Member States and because these parties are organisations, the concept of organisational behaviour and interorganisational trust is essential. ‘Trust towards organizations is about trust directed to an entity with a collective of people having a common goal and characterized by specific internal dynamics, culture and institutionalisation processes.’64x Levi-Faur et al., above n. 63, at 26.

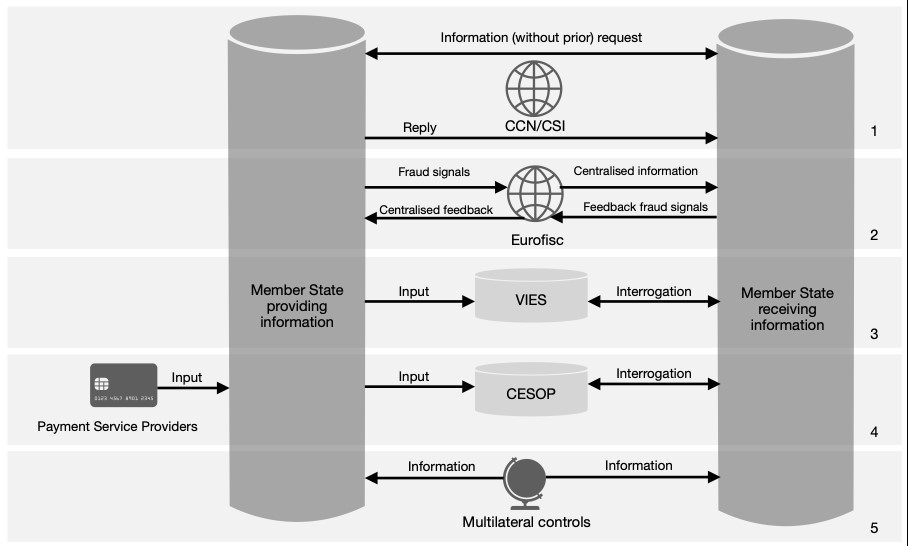

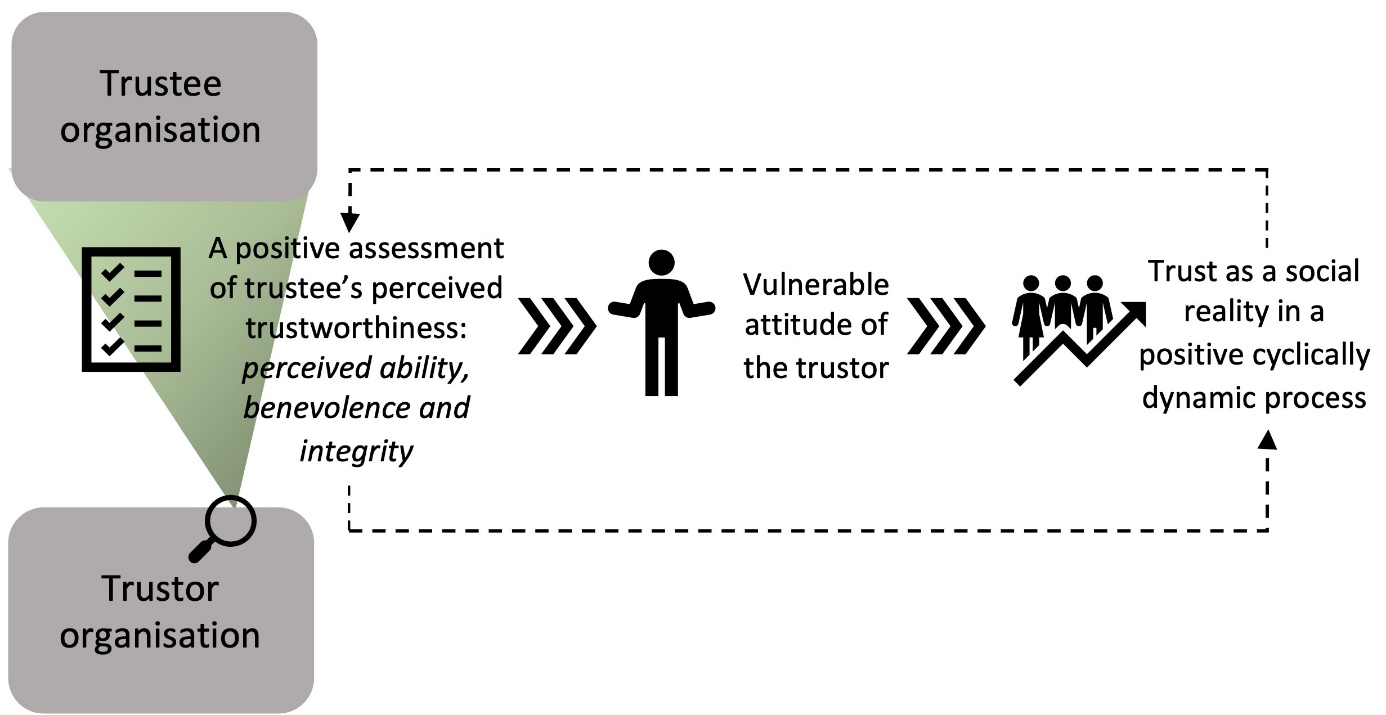

Interpersonal trust between the individuals within the two organisations that are in direct contact with each other and in the counterpart’s organisational system is the basis of organisational trust.65x G. Möllering, ‘Trust, Institutions, Agency: Towards a Neoinstitutional Theory of Trust’, in R. Bachmann and A. Zaheer (eds.), Handbook of Trust Research (2006) 355; J. Sydow, ‘How Can Systems Trust Systems? A Structuration Perspective on Trust-Building in Inter-organizational Relations’, in R. Bachmann and A. Zaheer (eds), Handbook of Trust Research (2006) 377. See also: Six, above n. 63, at 180. Trust in the individual representing the organisation (called the boundary spanner) can lead to trust in the organisation if the representative’s behaviour is seen as typical of the organisation.66x F. Kroeger, ‘Trusting Organizations: The Institutionalization of Trust in Interorganizational Relationships’, 19(6) Organization 743, at 747 (2012). And, conversely, organisational characteristics help to increase trust in the individual boundary spanner when the other party does not yet know that individual.67x F.E. Six and K. Verhoest, ‘Trust in Regulatory Regimes: Scoping the Field’, in F. Six and K. Verhoest (eds.), Trust in Regulatory Regimes (2017) 1, at 5. The boundary spanners make a subjective evaluation based on their expectations of the other organisation. In doing so, they look not only at the interpersonal contact with the other boundary spanner but also at the organisation as a whole, including its organisational and systemic characteristics. This is illustrated in Figure 3. Therefore, interorganisational trust can be defined as ‘a subjective evaluation made by boundary spanners, comprising the intentional and behavioural suspension of vulnerability on the basis of their expectations about a trustee organization’.68x P. Oomsels and G. Bouckaert, ‘Interorganizational Trust in Flemish Public Administration: Comparing Trusted and Distrusted Interactions Between Public Regulatees and Public Regulators’, in F. Six and K. Verhoest (eds.), Trust in Regulatory Regimes (2017) 80, at 81. Thus, when discussing trust in an organisation that operates within regulatory regimes, trust in organisations and systems (i.e. organisational or system level) and in the boundary spanner(s) (i.e. interpersonal level) is important.69x Six and Verhoest, above n. 67, at 4.The universal trust process as illustrated by Oomsels and Bouckaert.70x Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68. Illustrated explanation of the universal trust process. ©

Illustrated explanation of the universal trust process. ©

5.1 Creating Interorganisational Trust via the Universal Trust Process

Interorganisational trust is created via the universal trust process between two organisations. These two organisations are the trustor organisation and the trustee organisation. The trustor is the organisation that trusts. Hence, the trustor is the subject. The trustee is the organisation that is or must be trusted and is, therefore, the object of the trust of the trustor. Note that trust is reciprocal: trust between two organisations goes both ways. Hence, one organisation can be both a trustor and a trustee.71x See, e.g., the study of Six and Van Ees who measure trust in regulated actors two ways (Six and Van Ees, above n. 63) or the study of Oomsels and Bouckaert, who research the reciprocal and self-reinforcing process of trust building (P. Oomsels and G. Bouckaert, ‘Studying Interorganizational Trust in Public Administration: A Conceptual and Analytical Framework for “Administrational Trust”’, 37(4) Public Performance and Management Review (2014), at 577-604).

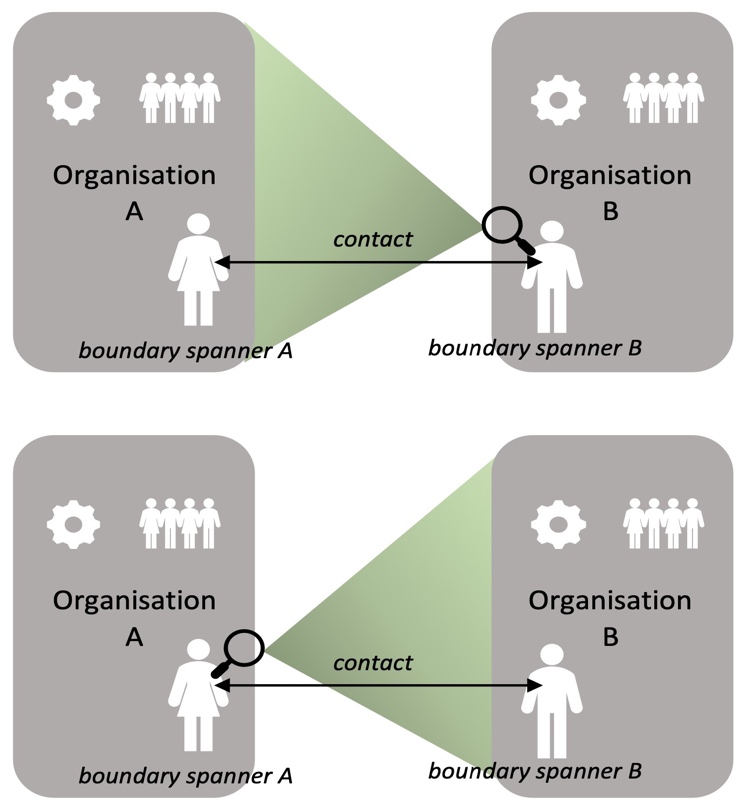

This universal trust process is illustrated in Figure 4 and can be explained as follows (see Figure 5).

The universal trust process starts with the trustor assessing the trustworthiness of the trustee. This assessment results in the perceived trustworthiness of the trustee. To assess the trustworthiness of the trustee, the trustor assesses:first, the perceived ability of the trustee (i.e. ‘[the] expectation that the other party has [the] competence to successfully complete its tasks’72x Ibid.);

second, the benevolence of the trustee (i.e. ‘[the] expectation that the other party cares about the trustor’s interests and needs’73x Ibid.); and

third, the integrity of the trustee (i.e. ‘[the] expectation that the other party will act in a just and fair way’74x Ibid., at 82.).75x The mentioned dimensions to assess trustee’s trustworthiness form the ABI-model of Mayer et al., which is probably most cited. R.C. Mayer, J.H. Davis, & F.D. Schoorman ‘An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust’, 20(3) The Academy of Management Review (1995). However, several dimensions and classifications have been proposed in the literature; ‘in another prominent classification, benevolence and integrity are taken together, referring to intentions, as empirically there is often not a clear distinction between these two dimensions, especially in organizational or system trust … Besides benevolence and integrity, competence as a manifestation of ability takes a central place in most conceptualizations of trustworthiness’. Levi-Faur et al., above n. 63, at 4.

Subsequently, when this perceived trustworthiness is assessed positively, the willingness of the trustor to suspend vulnerability increases, i.e. the trustor is ‘willing to assume that irreducible social vulnerability and uncertainty will be favourably resolved in the interorganizational interaction’.76x Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 82. Hence, if the trustor assesses the perceived trustworthiness of the trustee positively, this trustor will then dare to be vulnerable within the relationship because, based on the perceived trustworthiness of the trustee, the trustor expects that the interaction with the trustee will lead to a positive result and that vulnerabilities and uncertainties, e.g. in situations where the trustor depends on the trustee, will be resolved.

Interorganisational interaction aspects and the universal trust process, as illustrated by Oomsels and Bouckaert.77x Ibid.

Furthermore, according to Oomsels and Bouckaert, there must follow ‘a behavioural manifestation of risk-taking in dealings with the other party in order for trust to become a ‘social reality’ in the relationship … Finally, it is argued that the outcome from such risk-taking behaviour updates the trustors’ perceptions of the counterpart’s trustworthiness, rendering trust a cyclically dynamic process’.78x Ibid.

Hence, the fact that the trustor dares to be vulnerable when interacting with the trustee and takes certain risks of vulnerability and uncertainty in doing so ensures that trust becomes a social reality in the relationship between both organisations. The trustee will perceive the trustor’s actions as indications of trustworthiness and will probably act as expected, which will be perceived by the trustor as a confirmation of the trustor’s initial trust.79x Six and Van Ees, above n. 63, at 62. Such confirmation will result in a positive assessment of the trustee’s perceived trustworthiness for the future.5.2 How the Universal Trust Process is Influenced

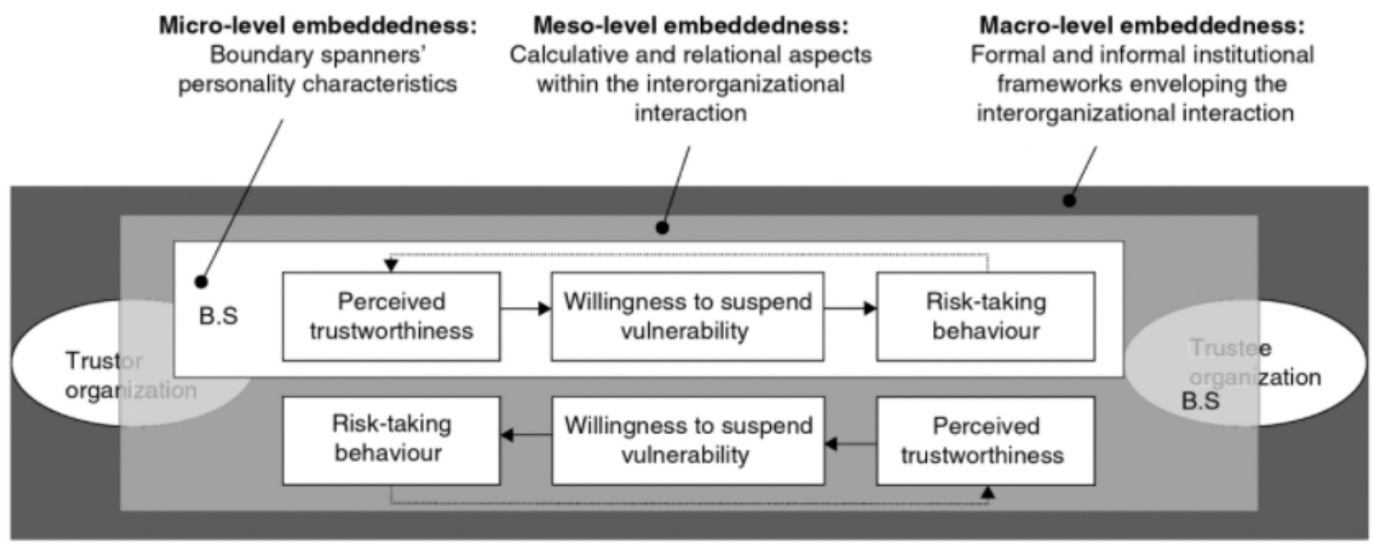

The universal trust process is influenced by different characteristics of the specific interorganisational interaction in which it occurs.80x Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 82. As stated before, the boundary spanners make a subjective evaluation based on their expectations of the other organisation. In doing so, they look not only at the interpersonal contact with the counterpart’s boundary spanner but also at the counterpart’s organisation as a whole, including its organisational and systemic characteristics. The context of boundary spanners’ interorganisational interactions on three different levels influences the universal trust process, as illustrated by Oomsels and Bouckaert in Figure 6.81x Ibid.

Figure 6 illustrates that the trust of the trustor in the trustee can be explained by examining how the trust evaluation of the trustor’s boundary spanner (i.e. the three dimensions of the universal trust process as illustrated in Figure 4 and explained in Figure 5)82x Figure 6 has the universal trust process mirrored twice to show that the same organisation can be both a trustor and a trustee. is influenced by the perceptions of the characteristics of the interorganisational interaction with the trustee at three different levels. Note that trust is reciprocal. Trust between two organisations goes both ways. Hence, one organisation can be both a trustor and a trustee.83x See above n. 70.5.2.1 The Micro Level

The micro level is illustrated in Figure 6 as the white area. The micro level represents the boundary spanners’ personality characteristics. This level concerns interpersonal trust between the interacting boundary spanners. This interpersonal trust entails that the initial attitude of the trustor’s boundary spanner is determined by the predisposing beliefs and expectations based on its trustworthiness beliefs about the trustee’s boundary spanner. These predisposing beliefs and expectations influence, e.g., how information is interpreted and thus impact the actions and the behaviour of the trustor’s boundary spanner towards the trustee’s boundary spanner.84x Six and Van Ees, above n. 63, at 61. See also: G. Dietz, ‘Going Back to the Source: Why Do People Trust Each Other?’, 1(2) Journal of Trust Research 215 (2011). According to Six and Van Ees, suspicious and cautious behaviour, or maybe even distrust, can easily occur because the cooperating regulatory parties come from different fields with, e.g., their own logic and sense-making processes.85x Six and Van Ees, above n. 63, at 63.

The following managerial implications are expected to lead to a positive trust-building process on the interpersonal level (i.e. micro level).86x Ibid., at 75 and 76. First, the cooperating organisations must be both task- and relationship orientated.87x ‘When only a task-orientation is present, self-fulfilling effects of beliefs and expectations are more likely and misattribution of causes for trouble are more prevalent, which hampers trust building.’ Six and Van Ees, above n. 63, at 75. Second, organisations must enter the process with good intentions and neutral to positive expectations. Third, it is important that an organisation strives to better understand and acknowledge the needs and interests of the counterpart and that, subsequently, both intentions and expectations are explicitly shared. Fourth, information sharing regarding trust buildings’ challenges88x ‘such as managing expectations, avoiding misperceptions, checking if interpretations and attributions are correct’. Six and Van Ees, above n. 63, at 74. is essential and must be well regulated and managed. Finally, all parties within the regulatory relationship must create opportunities for constructive escalation and actions aimed at improving relationships based on structural arrangements.89x Six and Van Ees, above n. 63, at 73-75.

5.2.2 The Meso- and Macro Level

The meso level is illustrated in Figure 6 as the light grey area. The meso-level represents the ‘direct experience with or evidence about a particular interaction or counterpart’.90x Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 85. On this level, the calculative and relational aspects within the interorganisational interaction between the boundary spanners affect trust. The calculative aspects entail consideration of costs and benefits based on available information about the counterpart and the extent of risk in the interorganisational interaction.91x Ibid. The available information may come from a direct source (i.e. from the trustor’s direct knowledge about the trustee) or other indirect sources (e.g. third-party audit reports or rumours about the trustee’s reputation).92x Ibid., at 86. The relational aspects that affect trust are, e.g., reciprocal behaviour,93x If certain positive behaviour (e.g. interpersonal care and concern) is reciprocated, interpersonal familiarity is established across their professional interaction experiences, which can result in more willingness to suspend vulnerability in interactions. Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 87. interpersonal familiarity94x ‘Interpersonal familiarity, associated with the age and the frequency of interactions, is linked to the emergence of shared values, mutual identity, interpersonal social norms, and a “social memory” that helps partners understand and interpret each other’s habits, customs and expectations’. Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 87. and power equality.95x Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 87.

The macro level is illustrated in Figure 6 as the dark grey area. The macro level stands for the (in)formal institutional frameworks enveloping the interorganisational interaction.96x Ibid., at 88. ‘Such institutions can be formal rules or roles, or informal routines, habits and social norms which provide a common ground for how to behave and what to expect from each other.’97x See above n. 64.

Oomsels and Bouckaert analysed how interorganisational trust is affected by boundary spanner’s perception98x Oomsels and Bouckaert note that their investigation only involves boundary spanners’ perception and that they did not study objective differences between (dis)trusted interactions. According to Oomsels and Bouckaert, this approach can be justified because interorganisational trust is argued to be a subjective evaluation of boundary spanners in interorganisational interactions. Furthermore, Oomsels and Bouckaert state that their theoretical model can apply to interorganistional trust problems beyond the investigated samples. Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 107. of interaction characteristics on an organisational or system level (i.e. meso- and macro level) independent of specific individuals. Oomsels and Bouckaert’s core findings have the following managerial implications. It is essential that the management of interorganisational trust understands the dimension-specific impact of particular interactions. Thus, an analysis of trust process dimensions in interorganisational interactions should be the start of managing interorganisational trust. This can be followed by an intervention aimed at shaping those interorganisational interaction characteristics with the strongest effect on any problematic trust process dimensions. Subsequently, it is important to consider that relational and calculative interorganisational interaction characteristics can have indirect effects on risk-taking behaviour under the condition that the internal causal dynamic of the trust process is safeguarded. Furthermore, interorganisational trust management should also consider how boundary spanners perceive and experience characteristics in their interorganisational interactions, and management should not only focus on introducing more institutional, calculative and relational ‘reasons for trust’ in the characteristics of interorganisational interactions. Finally, studying and managing social structures and the interaction between a trustor and trustee within social structures, which allows for long-term interaction between these characteristics, is necessary.99x Oomsels and Bouckaert (2017), above n. 68, at 105-7.

-

6 The Practical Implementation of the VAT E-commerce Rules and the Lack of Trust

Now that we know more about the VAT e-commerce context (Sections 3 and 4) and interorganisational trust (Section 5), it is important to assess how the VAT e-commerce rules are implemented in practice by the Member States (Section 6.1) and whether a lack of trust between the Member States is perceived (Section 6.2). Because, if a lack of trust is perceived, the theoretical model of interorganisational trust and its implications might help in improving the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules.

6.1 The Practical Implementation of the VAT E-commerce Rules

Each EU tax administration is different owing to its specific organisational characteristics and therefore performs differently. All the different enforcement approaches result in differences in the practical implementation of EU VAT law by the Member States.100x Mercedes Garcia Munoz and Saulnier, above n. 10. See also: D. Pîrvu, A. Duţu, & C.M. Mogoiu, ‘Clustering Tax Administrations in European Union Member States’, 63 Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 110 (2021). Variation in the degree of practical implementation need not be a problem in itself. Member States can reduce their shortage of, e.g., information, resources or people by joining forces. The Regulation on administrative cooperation provides for enough legal ground for EU tax administrations to be involved in different administrative cooperation mechanisms.101x Merkx, above n. 11, at 45. Besides, financial support is provided for by the European Commission.102x European Commission Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union, Oxford Research, Coffey, & Economisti Associati, Mid-term Evaluation of the Fiscalis 2020 Programme: Final Report, TAXUD/2015/CC/132 (2018), at 6. However, it appears from research on the effectiveness of VAT collection and administrative cooperation that the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules (as discussed in Section 3) and the Regulation on administrative cooperation (as discussed in Section 4) is lacking.103x See above n. 11. Many reports conclude that not all the Member States adequately use the opportunities provided for by the European Commission regarding administrative cooperation.104x E.g., European Commission, Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the Application of Council Regulation (EU) No 904/2010 Concerning Administrative Cooperation and Combating Fraud in the Field of Value Added Tax, COM(2014) 71 final (2014), at 1-17; European Court of Auditors, Tackling Intra-Community VAT Fraud: More Action Needed, Special Report No 24 (2015), at 1-54; European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11; Mercedes Garcia Munoz and Saulnier, above n. 10. The Member States barely control105x This is evident from the ninth report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on VAT registration, collection and control procedures. The report shows that the vast majority (16 of the 28 EU Member States) did not carry out any MOSS checks in 2019. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Ninth Report from the Commission on VAT Registration, Collection and Control Procedures Following Article 12 of Council Regulation (EEC, EURATOM) No 1553/89, 7 April 2022, COM(2022) 137. and exchange information regarding e-commerce transactions,106x European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11, secs. 54-57. In the opinion of the European Court of Auditors, the risk exists that tax administrations of the Member States of consumption will not use the administrative cooperation arrangements to request information from the country where the supplier is identified or registered. European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11., at 11, 22, 24 and 25. and a coordinated exchange of experience between tax administrations implementing e-commerce controls does not exist.107x National Audit Office of Lithuania, above n. 11, at 5. Also, the European Court of Auditors concludes that there is insufficient and/or no effective administrative cooperation between the Member States.108x European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11. Furthermore, the Member States seem unwilling to cooperate because, on the one hand, they seem to think that the use of administrative cooperation instruments will result in additional VAT income for another Member State and, on the other hand, that the information requested will not be provided in time and will therefore not contribute to tax audits.109x European Commission, Report from the Commission to the Council and European Parliament on the Application of Regulation (EEC) No. 218/92 (Third Article 14 Report), COM(2000) 28 final (2000), at 22; European Commission (2014), above n. 104, at 9 and 10; National Audit Office of Lithuania, above n. 11; European Commission and Deloitte (2016b), above n. 11, at 112; Netherlands Court of Audit, above n. 11; Merkx, above n. 11, at 45 and 46. Regarding the latter, the European Commission states that ‘amending Regulation (EU) 904/2010 would not bring any added value in this respect as the instruments themselves are appropriate. It is their implementation in certain Member States that needs to be addressed’.110x European Commission (2017), above n. 13, at 9. By ‘implementation’ the European Commission probably meant the practical implementation of Council Regulation 904/2010 because a Council Regulation applies directly to the Member States and does not have to be formally implemented (i.e. transposed) into national law. However, little incentive exists for the Member States to change their practice and ensure a quick response to information requests now that the ECJ ruled in the Hydina case,111x See above n. 61. as discussed in Section 4.1, that exceeding the time limits of Article 10 of the Regulation on administrative cooperation does not have any direct112x Taxpayers cannot derive any rights from Council Regulation 904/2010 (see sec. 4.1 of this article), so the European Commission will have to initiate an infringement procedure under Arts. 258, 259 and 260 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. European Commission, Communication from the Commission – EU Law: Better Results Through Better Application, 2017/C 18/02 (2017); European Court of Auditors, Landscape Review – Putting EU Law into Practice: The European Commission’s Oversight Responsibilities under Article 17(1) of the Treaty on European Union, No. 7 (2018), at 4 and 7. consequences.113x Cf. Janssen and Verbaan, above n. 55.

6.2 Concerns of a Lack of Trust Between the Member States

Because VAT, which is due on some e-commerce transactions, accrues to one Member State but is collected by another and the Member States depend on each other’s enforcement efforts in this, a high degree of cooperation and trust is needed.114x P. Genschel, ‘Why No Mutual Recognition of VAT? Regulation, Taxation and the Integration of the EU’s Internal Market for Goods’, 14(5) Journal of European Public Policy 743, at 755 (2007); European Commission (2016), above n. 12; R. de la Feria, ‘The Definitive VAT System: Breaking with Transition’, 3 EC Tax Review 122 (2018); European Commission (2018), above n. 53, at 61; Merkx, above n. 11, at 29. As stated, the degree of cooperation between the Member States is not high. Regarding the limited degree of cooperation between the Member States, concerns of a lack of trust have been expressed in the literature. The fact that not all Member States (actively) participate in the administrative cooperation mechanisms, such as Eurofisc,115x See above n. 51. that the rule of law is not always respected in all Member States, e.g., regarding the time limits of Article 10 of the Regulation on administrative cooperation, as discussed in Section 4, and that some Member States might use the VAT revenues that accrue to the other Member States as a political bargaining chip,116x S.B. Cornielje, ‘Een oude mug en een krakkemikkig kanon’, 7294(139) Weekblad Fiscaal Recht 834 (2019); S.B. Cornielje, ‘De (on)begrensde mogelijkheden van de Europese btw’, SSRN Electronic Journal, at 19 (2021). result in tensions between the Member States.117x See e.g., M. Lamensch, ‘Trust: A Sustainable Option for the Future of the EU VAT System?’, 30(2) International VAT Monitor 53 (2019). The Member States do not have the political will to take the actions necessary to move to ‘a genuine single EU VAT area for the Single Market’118x European Commission (2016), above n. 12, at 4. because, according to Sutton, ‘national finance ministers simply have never found the unanimous consensus to abandon national fiscal sovereignty’.119x Sutton, above n. 1, at 2. This, e.g., also seems to be the case regarding the unsuccessful proposal for a definitive VAT system, which was, according to De La Feria, not successful because it was ‘impossible to secure the necessary unanimous agreement of all Member States, primarily as a result of a lack of mutual trust between them’.120x de la Feria, above n. 114, at 122. Traversa even regards this as the most important reason and urges the intensification of (administrative) cooperation between the Member States. ‘Some Member States are indeed extremely reluctant to accept a system where taxes would be systematically collected on behalf of others. Some invoke as an additional argument the lack of motivation for a tax administration to assess and collect a tax that would not accrue to the national budget. Sometimes, what seems to be at stake appears to be the overall efficiency or even the integrity of certain domestic tax administrations of EU Member States.’121x Traversa, above n. 7, at 245 and 246. Cf. Janssen and Verbaan, above n. 55.

-

7 The European Commission’s Plan to Improve Trust Between the Member States

The lack of trust between the Member States is worrying and needs to be tackled. In the first place, this must be done by the Member States. However, as stated in Sections 4.1 and 6.1, owing to the ECJ judgment in the Hydina case,122x See above n. 61. Member States have little incentive to change their practice. Therefore, the European Commission must, in the author’s opinion, take action, especially because it is one of the European Commission’s responsibilities to monitor and ensure the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules, including the Regulation on administrative cooperation. The European Commission could modify current regulations or propose new legislation and make policy that could foster trust. Furthermore, the European Commission could assist the Member States in the practical implementation of the Regulation on administrative cooperation by using, e.g.,123x J. Tallberg, ‘Paths to Compliance: Enforcement, Management, and the European Union’, 56(3) International Organization 609, at 610, 611 and 614 (2002). capacity building124x E.g. via the Commission guidelines on VAT. ‘Commission guidelines on VAT are explanatory notes and other documents produced by the Commission services in order to provide practical and informal guidance about how particular provisions of EU VAT law should be applied. Guidelines issued by the Commission’s Directorate General for Taxation and Customs Union only contain practical and informal guidance about how EU law should be applied and are not legally binding.’ European Commission, Commission Guidelines, https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/commission-guidelines_en (last visited 19 January 2022). and rule interpretation.125x E.g. via the Fiscalis Programme, ‘the Fiscalis programme finances activities such as: communication and information-exchange systems, MLC – multilateral controls, seminars and project groups, working visits, training activities and other similar activities.’ Butu and Brezeanu, above n. 52, at 98. When necessary, the European Commission must use its enforcement powers126x The European Commission can use, as a last resort, the infringement procedure under Arts. 258, 259 and 260 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. European Commission (2017), above n. 112; European Court of Auditors (2018), above n. 112. to ensure that EU law is properly applied and enforced by the Member States.127x R. Baldwin, M. Cave, & M. Lodge, Understanding Regulation – Theory, Strategy, and Practice (2012), at 389 and 390; European Court of Auditors (2018), above n. 112, at 7; European Commission, Member States’ Compliance with EU Law in 2018: Efforts are Paying Off, But Improvements Still Needed, press release (2019), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_3030 (last visited 19 January 2022).

Improving the administrative cooperation between the Member States has been on the agenda of the European Commission for a while.128x Mercedes Garcia Munoz and Saulnier, above n. 10. It was, e.g., part of the 2016 and 2020 Action Plans129x See above n. 12. from the European Commission. In these action plans, the European Commission also recognises that trust between the Member States is essential for the proper functioning of the VAT system and that the Member States must cooperate in order to ensure that EU tax policy works in a global and digitalised economy.130x European Commission (2016), above n. 12, at 3 and 7; European Commission (2020), above n. 12, at 13; Sutton, above n. 1, at 9. However, in the author’s opinion, neither these action plans nor the current legislation and regulations (as described in Section 4) nor the European Commission’s plans for modernising the VAT system contain sufficient measures to adequately address the lack of trust between the Member States.131x Cf. Janssen and Verbaan, above n. 55. E.g., the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) researched132x Mercedes Garcia Munoz and Saulnier, above n. 10. how the VAT system could be modernised and how the information exchanges and compliance levels could be improved to reduce the VAT gap. The EPRS assessed the following three scenarios for the modernisation of the current VAT system as described in Sections 3 and 4. The first scenario entails extended cooperation with a more automatic exchange of information and the further deployment of the OSS system. Subsequently, the second scenario contains extended cooperation with a VAT definitive regime and the further deployment of the OSS system. And, the third and last scenario entails the establishment of an EU treasury and VAT administered at the EU level (i.e. a centralised and united approach in which the EU gets more leadership in collecting and administering VAT). According to the EPRS, the third scenario is ambitious but ‘rather unlikely to gather sufficient support at the current juncture and would also require substantial Treaty change’,133x Ibid., at II. while the first and second scenarios ‘are most likely to be implemented in the coming years’.134x Ibid., at 40. The EPRS report states that there exists a certain apathy among the Member States regarding the plans for modernisation due, among others, to diverging perspectives, which must be addressed. Given the importance of VAT in the EU fiscal framework and the increasing capital movement, digitalisation, globalisation, adoption of common solutions at an EU level is highly necessary and relevant according to the EPRS.135x Ibid., at I, II, 1, 19 and 41. After all, in today’s globalised economy, the Member States and their tax administrations can no longer work independently of each other. However, the EPRS report does not address concrete measures to address the lack of trust between the Member States.

Traversa states: ‘In light of current geopolitical developments, it appears questionable whether the European Union can afford open mistrust between Member States and EU institutions, or between Member States themselves.’136x Traversa, above n. 7, at 245. Hence, any risk of creating major tension in the relationship between the Member States must be eliminated,137x Lamensch, above n. 117, at 54. and, therefore, the influence of trust in this relationship must be adequately considered when defining common solutions at the EU level. This is especially the case now that the first two scenarios for the modernisation of the VAT system will probably be implemented in the coming years. After all, automatic exchange of information alone will not bring about improvements, and bringing the OSS system up to speed will escalate tensions between the Member States as long as trust between them is not improved.138x Cf. Janssen and Verbaan, above n. 55. -

8 The Contribution of Trust to the Practical Implementation of the VAT E-commerce Rules

Based on the Sections 6 and 7, it can be concluded that, on the one hand, owing to the ECJ judgment in the Hydina case,139x See above n. 61. Member States have little incentive to change their practice, and, on the other hand, the European Commission’s plans are insufficiently focused on addressing the lack of trust between the Member States. In the author’s opinion, this must change, and the level of trust between the Member States must be improved.

The theoretical lessons of Section 5 teach us that interorganisational trust (i.e. trust between the Member States) is created via the universal trust process, which is influenced by different characteristics of the specific interorganisational interaction in which it occurs. As the universal trust process can be influenced, it is interesting to examine how these implications can be applied to the VAT e-commerce context (Section 8.1) and whether further research is necessary (Section 8.2).8.1 The Implications Applied to the VAT E-commerce Context

The model of organisational behaviour and trust, the universal trust process and its implications are well applicable to the described VAT e-commerce context. The Member States’ tax administrations, which are organisations, rely on each other for the practical implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules. This places them in a cooperative relationship where trust plays an important role as one Member State under the OSS system has to partially outsource the collection of VAT to another Member State. The universal trust process between the Member States is influenced on a micro-, meso- and macro level. Note that trust is reciprocal: trust between two Member States goes both ways. Hence, one Member State’s tax administration can be both a trustor and a trustee.

Within the VAT e-commerce context, the micro level could be seen as the inspectors and representatives140x E.g. the Member States’ representatives of the OSS, the Eurofisc liaison officials from the twenty seven Member States, the inspectors at MLCs, the officials from national tax administrations and Ministries of Finance that come into contact in the Standing Committee on Administrative Cooperation (SCAC) meetings, and representatives of the Member States in the VAT committee. of the Member States working together as boundary spanners on MLCs or exchanging information. The fact that the representatives working together come from different fields affects trust at the micro level. An example of influencing factors on the micro level within the VAT e-commerce context is the language issues.141x According to the European Court of Auditors, the use of information exchanges (on request or spontaneously) on e-commerce is limited (European Court of Auditors (2019), above n. 11, points 54-57; Merkx, above n. 11, at 46) and according to the European Commission, language issues are one of the reasons causing this (European Commission (2014), above n. 104, at 9).

The meso-level in the context of VAT e-commerce involves the organisation of the national tax administrations as a whole. An example of influencing factors on the meso-level within the VAT e-commerce context is the lack of (human and technical) resources and internal procedures.142x According to the European Commission, the lack of (human) resources and internal procedures also accounts for the limited use of information exchanges (on request or spontaneously) on e-commerce. European Commission (2014), above n. 104, at 9. Furthermore, reports on the functioning of the OSS system (and MOSS system, which is the predecessor of the OSS system) are issued on a regular basis. E.g., the report by the European Commission,143x Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, above n. 105, at 21. as referred to in Section 6.1, showed that in 2019 (when the MOSS system was still in place) the vast majority of the Member States did not carry out any checks on the MOSS declarations or carried out very few. Hence, when it comes to a Member State of identification, it largely concerns VAT receipts from the other Member States of consumption, which the Member State of identification did not check or hardly checked.144x M.M.W.D. Merkx and A.D.M. Janssen, ‘Opinie: Laat de OSS geen vrijplaats worden!’, NLF Opinie 2022/17. These reports are examples of indirect sources that could influence trust between the Member States on the meso-level.The macro level in the context of VAT e-commerce concerns not only the country to which the tax administration belongs and all the legislation and social norms to which it is subject (e.g. the different cultures within the EU) but also the formal and informal institutional frameworks and systems, which can indicate the performance of the Member States. The Netherlands and Germany, e.g., had requested a postponement of the implementation of the VAT e-commerce rules until January 2022. The Netherlands requested a postponement because of the extent of the changes and the status of the existing ICT facilities. The changes would require new systems to be built, and, therefore, the VAT e-commerce package could not be implemented in the Netherlands until 1 January 2022.145x NLFiscaal, ‘Kamerbrief update btw e-commerce; kabinet wil extra uitstel tot 1 januari 2022’, NLF 2020/1954. Another example is the double VAT taxation on imports that arose, among others, because some Member States are not in a position to validate the IOSS number in a full customs declaration because of their IT systems and technical problems in the Member State of importation.146x European Commission (2022), Proposed Solution to Regularise Double Taxation in the IOSS VAT Return, GFV No 115. The Bulgarian tax administration and its systems were, e.g., found to have fallen victim to hackers in 2019. The Dutch tax administration then decided to temporarily stop providing data to the Bulgarian tax administration until a robust, secure environment was restored.147x Kamerstukken II 2020, Beveiliging gegevensuitwisseling, nr. 2020-0000034510.