-

1 Introduction

Empirical legal research (ELR) has a long-standing tradition, at least in the United States. There, the roots of legal realism may be placed in the early 1900s, with the first publication of ELR placed in 1911.1xH.M. Kritzer, ‘Empirical Legal Studies Before 1940: A Bibliographic Essay’, 6 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (2009), at 926. The Law and Society Association (LSA) was founded decades later, in 1964, and the first issue of the Law and Society Review (LSR) was published in 1966.2x www.lawandsociety.org/history.html (last accessed 8 October 2018). The rise of the Empirical Legal Studies (ELS) movement can be placed around the year 2000.3xM. Heise, ‘The Past, Present, And Future of Empirical Legal Scholarship: Judicial Decision Making and the New Empiricism’, University of Illinois Law Review (2002), at 819; R.H. McAdams and T.S. Ulen, ‘Introduction to the Symposium on Empirical and Experimental Methods in Law’, University of Illinois Law Review (2002). Soon after, the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (JELS), first published in 2004, was established, as was the Society for Empirical Legal Studies (SELS), which held its first Annual Conference on Empirical Legal Studies (CELS) in 2006.4xP. Cane and H.M. Kritzer, The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research (2010), at 1026. In addition, several centres on ELR have emerged.5xL.A. Gordon, The Empiricists: Legal Scholars at the Forefront of Data-Based Research (2010). This article refers to ELR rather than ELS to describe empirical legal research, because of ELS’ connotation with quantitative analysis (see below).

The rise of ELR in the US can be further demonstrated by the numerous publications in a variety of fields and journals. The proportion of publications with empirical analysis has risen significantly over time,6xM. Heise, ‘An Analysis of Empirical Legal Scholarship Production, 1990-2009’, 2011 University of Illinois Law Review (2011), at 1739. See also R.C. Ellickson, ‘Trends in Legal Scholarship: a Statistical Study’, 81 Journal of Legal Studies (2000) 517, at 528-29 (researching the 1982-1996 period and finding that ‘[t]he indexes for both empiric! and quantitate! (…) are virtually flat from 1982 to 1996 (…) [but that] the indexes for both statistic! Significan! And Table 1 almost double over the same time frame’, which suggests that ‘law professors and students have become more inclined to produce (although not consume) quantitative analysis’) and T.E. George, ‘An Empirical Study of Empirical Legal Scholarship: The Top Law Schools’, 81 Indiana Law Journal (2006) 141, at 147 (extending the Ellickson study to the 1994-2004 period), both researching the number of references to empirical legal scholarship. even though the proportion of empirical articles as opposed to non-empirical articles remains low.7xS.S. Diamond and P. Mueller, ‘Empirical Legal Scholarship in Law Reviews’, 6 Annual Review of Law and Social Science (2010) 581, at 581, 587 (reporting that 5.7% of the US law review articles contain original empirical data, with original defined as data collected by the researcher himself or herself). Furthermore, a substantial proportion of law review articles have been found to report empirical research conducted by others than the authors of the article.8x Ibid., 581, 587. See also Heise, ‘The Past, Present, And Future of Empirical Legal Scholarship: Judicial Decision Making and the New Empiricism’; McAdams and Ulen, ‘Introduction to the Symposium on Empirical and Experimental Methods in Law’. For examples of ELS research from before 1940, see Kritzer, ‘Empirical Legal Studies Before 1940: A Bibliographic Essay’. LSA research and ELS can be considered extremes on the same spectrum of ELR. LSA research has adopted a ‘Big Tent’ policy, making it somewhat undefined in terms of topics and the methods and techniques used:Although they share a common commitment to developing theoretical and empirical understandings of law, interests of the members range widely. Some colleagues are concerned with the place of law in relation to other social institutions and consider law in the context of broad social theories. Others seek to understand legal decision-making by individuals and groups. Still others systematically study the impact of specific reforms, compliance with tax laws, the criminal justice system, dispute processing, the functioning of juries, globalization of law, and the many roles played by various types of lawyers. Some seek to describe legal systems and identify and explain patterns of behavior. Others use the operations of law as a perspective for understanding ideology, culture, identity, and social life. Whatever the issue, there is an openness in the Association to exploring the contours of law through a variety of research methods and modes of analysis.9x www.lawandsociety.org/history.html (last accessed 8 October 2018).

In contrast, ELS researchers arguably pose and answer more pragmatic questions than their LSA counterparts, focusing more on questions that have policy and practical relevance and less on theory-driven questions.10xE. Mertz and M.C. Suchman, ‘A New Legal Empiricism? Assessing ELS and NLR’, 6 Annual Review of Law and Social Science (2010), at 555. According to Eisenberg, the founding father of the ELS movement in the US, ELS was intended to deal with matters regarding how the legal system works, ensuring the relevance for policy makers, litigants and judges.11xT. Eisenberg, ‘Why Do Empirical Legal Scholarship?’, 41 San Diego Law Review (2002) 1741, 1741.

Despite its popularity, ELS has also been criticised.12x See, for example, L. Epstein and G. King, ‘The Rules of Inference’, 69 University of Chicago Law Review 1 (2002). It has been argued that its role remains significantly underdeveloped and incidental, particularly in comparison to other disciplines forming part of the ‘social sciences’, such as political sciences and sociology, where empirical methods and research designs have become indispensable tools.13xM. Heise, ‘The Importance of Being Empirical’, 26 Pepp L Rev (1999) 807, 812.

Has ELR also become well established in Europe? In Europe, like in various countries, the methodology of law and legal research has become a debated issue. What was once a primarily national discipline has become more European, more international and more multi-interdisciplinary, with the discipline transitioning from (implicit) traditions to a stronger emphasis on methodology.14xR. van Gestel and H.-W. Micklitz, ‘Revitalizing Doctrinal Legal Research in Europe: What About Methodology?’, EUI LAW 2011/05 (2011), at 2. Moreover, in several countries it can be observed that legislators and policy makers are calling for more empirical research, that scholars seem to welcome more ELR, and that a substantial part of Judiciary Councils’ research is empirical.15xX.E. Kramer, ‘Editorial: Empirical Legal Studies in Private International Law’, Nederlands Internationaal Privaatrecht (2) (2015), at 195. Although ELR was slower to catch on in other corners of the world than the US, no longer is the interest in empirical legal research confined to the US (and perhaps to socio-legal studies in the UK); there are nowadays active communities of empirical legal researchers in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Germany, Israel and Japan.16xCane and Kritzer, above n. 4; L. Epstein and A.D. Martin, An Introduction to Empirical Legal Research (Oxford University Press 2014).

The presumed rise of ELR in Europe can be further illustrated by various conferences, workshops and communities that have taken place or have originated. In the Netherlands, for example, there has been a recent explosion of activities. In July 2016, the Conference on Empirical Legal Studies Europe (CELSE) was held in Amsterdam. There were conferences on ELR organised at the Dutch Supreme Court (December 2016) and by the Dutch Law and Society Association (VSR) (January 2017). In 2016, the Empirical Legal Studies initiative (ELSi), hosted by the Ius Commune Research School, was created, which organised a workshop on a starters kit for novices in the field of ELR (September 2017). Additionally, ELR workshops were held in Amsterdam (October 2016), Rotterdam (May 2017) and Leiden University (October 2017). At the European level, NoLesLaw, has emerged, a network of scholars ‘who seek to increase the quality, scale, and relevance of legal empirical research’.17x http://noleslaw.net (last accessed 8 October 2018). Furthermore, in May 2018 the second edition of the Conference on Empirical Legal Studies Europe (CELSE) was held at Leuven University.

Despite these events, the popularity of ELR in Europe is up for debate. Information on the use of empirical research in legal scholarship is lacking, and anecdotal evidence unreliable. Moreover, the fact that events are organised does not mean ELR is conducted more frequently. In this article, we address the knowledge gap about the prevalence of ELR in Europe by measuring the proportion of ELR articles as part of the number of journal articles published in a large number of European-based journals. Considering we do not find convincing support for the supposed rise of ELR, we seek an explanation for this finding, and subsequently provide directions for overcoming (if one desires to do so) the obstacles ELR currently faces.

This article is divided into five sections. In Section 2 we discuss our hypotheses regarding the journal analysis. In Section 3 we provide a theoretical framework of what ELR is and how to translate it into an empirical, observable concept in order to measure the popularity of ELR. The design of the empirical study and the results will subsequently be discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 will be dedicated to identifying and understanding the obstacles that explain why ELR is not more popular in Europe (and possibly beyond), and how to overcome these obstacles. -

2 Hypotheses

In order to test whether ELR has become more prevalent in Europe, an analysis of journal articles published in legal journals was conducted. European-oriented journals were inspected for empirical articles focusing on a 10-year period (2008-2017).

We were also interested in other predictors for the percentage of empirical articles in European-based legal journals. For this, we anticipated that ‘extra-legal’ journals that indicate the presence of another discipline (e.g. criminology, economics) or whose focus go beyond the law (e.g. criminal justice as opposed to criminal law) are more inclined to publish empirical articles than ‘traditional’ legal journals (H1). This relationship is partly tautological, as the reason some journals are ‘extra-legal’ is likely related to the fact that they include more empirical work than other journals. Nevertheless, ‘extra-legal’ journals also include non-empirical work, and not all extra-legal journals necessarily have an empirical focus.

Similarly, we expected that some topics would receive more empirical attention than other topics. Given the societal and political attention for crime-related topics, we particularly anticipated that journals focusing on criminal justice would contain a higher proportion of empirical work than journals focusing on other topics or domains (H2). Furthermore, we expected that older journals would contain more empirical work than journals that were more recently established (H3), because (a) older journals are more well established for a reason (i.e. to address trends) and (b) our impression was that the number of specialised journals have risen over time, with many of them having an important focus on legal practice as the market for legal practice seems larger than the market for legal academia.. For similar reasons, higher-ranked journals (as in: high-quality journals) were expected to contain a higher percentage of empirical work than lower-ranked journals (H4).

Moreover, the article investigates the relation between the year in which the articles were published and the aforementioned predictors. We were interested in whether differences regarding the increase (or decrease) of the percentage of empirical articles depended on the scores of any of the other factors. More specifically, we hypothesised that:The increase in the proportion of empirical articles is lower for criminal justice journals than for other journals (H5), since publishing empirical work has been more common in criminal justice journals than in other journals.

For the same reason, the increase in the proportion of empirical articles is lower for extra-legal journals than for other legal journals (H6a).

Alternatively, the increase in the proportion of empirical articles is higher for extra-legal journals than for other legal journals (H6b), because extra-legal journals may be more susceptible to an increased demand of empirical research than traditional legal journals, which are likely to be more conservative.

The increase in the proportion of empirical articles is higher for older journals than for other legal journals (H7), as older journals might adapt to the audience’s needs and wants better than more recently established journals.

For the same reason, the increase in the proportion of empirical articles is higher for high-ranked journals than for low-ranked journals (H8).

-

3 What Is ELR?

Delineating ELR presupposes a notion of what is ‘empirical’ and what is ‘legal’. With regard to the term ‘legal’, ELR presumes the presence of a legal element, a connection to the legal world. What is considered legal, non-legal or extra-legal, can vary substantially. A judge might mostly or exclusively find information relevant that determines the outcome of a case, whereas a policy maker may see more value in obtaining information to measure the impact of the law and whether the law should be changed. Similarly, a scholar with an instrumental view on the law might be less concerned with maintaining the law than a doctrinally oriented scholar who aims to preserve certain legal concepts and the relationships between those concepts. The differing perceptions about what is legally relevant in a given context impacts the view on what is considered ‘legal’ and can be subject to change over time. Consequently, discerning what is ‘legal’ and what is ‘a legal journal’ can be a daunting task. In this article, we avoid the issue of having to define what is ‘legal’ by sampling journals from a journal ranking that includes a variety of legal journals.

The answer to the question of when ELR can be considered empirical legal research is also not straightforward. One possibility is to define ELR in terms of the object of the research. In its most general sense, ELR may then be described as gathering knowledge by means of observing reality. The issue with such a definition, however, is that it leads to a problem of indistinguishability, as ‘reality’ includes laws, statutes, cases and legislative history. As a result, the analysis of case law, legislation and legislative history as commonly conducted or accepted in the legal domain has to be considered empirical under this definition.18xR. Korobkin, ‘Empirical Scholarship in Contract Law: Possibilities and Pitfalls’, University of Illinois Law Review 1033, (2002) at 1035 (fn 3). Defining ELR in terms of gathering knowledge by means of observing reality would then become counterintuitive, as it contradicts the intuition that empirical research is different from doctrinal research.

Another attempt at describing ELR is to define it as systematically analysing the effects on the law (what the law ‘does’) on the basis of observations.19xDiamond and Mueller, above n. 7; C.E. Schneider and L.E. Teitelbaum, ‘Life’s Golden Tree: Empirical Scholarship and American Law’, Utah Law Review (2006), at 53; S.S. Diamond, ‘Empirical Marine Life in Legal Waters: Clams, Dolphins, and Plankton’, Univ Ill Law Rev (2002) at 803, 805. The problem of this definition is that it excludes empirical approaches to determine what the law is or what the law should be.20x‘Should’ according to, for example, certain respondents or interviewees. Alternatively, ELR can be defined in terms of the way it is conducted, that is, how a research problem is researched as opposed to what problem is researched. This type of definition is commonly used within the context of ELS. A limitation of ELS, however, is that it seems to mostly rely on statistical or quantitative methods. The quantitative focus was, for example, visible in the first European CELS version (CELSE), which was held June 2016: ‘Empirical analysis is understood to encompass computer-based text-mining techniques and, more generally, any systematic approach to quantitative data analysis’.21x See http://acle.uva.nl/content/events/conferences/2016/06/conference-on-empirical-legal-studies-2016---21-and-22-june-2016.html (last accessed 8 October 2018). Most of these definitions bear the disadvantage that forms of qualitative research are excluded, such as interviews or participant observation.22xFor example, Heise, ‘The Importance of Being Empirical’, 810-11; C.A. Nard, ‘Empirical Legal Scholarship: Reestablishing a Dialogue Between the Academy and the Profession’, 30 Wake Forest Law Review (1995), at 348-61.

In this article, we follow the approach of defining ELR in terms of how the research is conducted, but without limiting ourselves to quantitative methods. We therefore include, what is referred to as, qualitative studies. However, it may be argued that the way in which ELR is conducted is similar to how research is generally conducted. For example, the process of synthesising cases resembles hypothesis testing in the social sciences. Gionfriddo, using the hypothetical problem of deriving general rules from a number of court decisions in order to determine whether a child toy is considered dangerous, illustrates the role of hypothesis testing when synthesising cases to determine the law.23xJ.K. Gionfriddo, ‘Thinking Like a Laywer: The Heuristics of Case Synthesis’, 40 Texas Tech Law Review 1 (2007) (defining case synthesis in fn 1). She develops and subsequently tests hypothesis about how the liability determination can be explained: is it the weight of the toy (light / heavy), the shape of the toy (round / angled / oval) or a combination of weight and shape?24x Ibid., 31.

In specifying how ELR differs from non-ELR, consequently avoiding overlap with doctrinal (non-empirical) research, we distinguish ELR from non-ELR (i.e. legal research not being empirical) in terms of the research methods that are used or applied. In this respect, we discern between (1) methods of data collection and (2) methods of analysis. Methods of data collection that are considered ELR in this research include observation (i.e. gathering new data by observing behaviour) and questioning (i.e. collecting new data by means of asking questions, either through interviews, a questionnaire, or both), as these methods intend to measure reality but are not commonly applied in non-ELR. Regarding the use of already available data, for example data that were collected and available through archives, data that are documented as the outcomes of administrative processes, or data that follow from the technological developments in the form of ‘Big Data’, we focused on the method of analysis, meaning that we required the research to have made calculations (e.g. frequencies, means, coefficients). When qualitative data of others (not collected by the authors), such as interview data and questionnaire data, was re-analysed, we regarded this as empirical if the data itself was analysed and the analysis went beyond merely mentioning results reported by others.

Following the definition deployed in this article, the analysis of law, legislative history, jurisprudence and literature can be classified as either empirical or doctrinal research, depending on the way the material is studied. The same applies to scholarship that analysed case law. A textual interpretation of case law and a case law comparison will then be considered doctrinal legal research, whereas making calculations would be considered ELR.

Defining ELR as research that uses certain methods of data collection or analysis does not demarcate ELR from other types of research that have legal and empirical elements in them. ELR, for example, overlaps with various ‘Law and …’ movements such as Law and Psychology, Law and Economics, Law and Anthropology as well as with criminology, victimology and legal realism. We do not consider this an issue. The existence of such disciplines or movements and their proven success presumably contributed to the acceptance of ELR. We will therefore not discern between ELR and, for example, criminology, victimology, or Law and Economics research. -

4 The Prevalence of ELR in European Journals

In order to test whether ELR has become more prevalent in Europe, an analysis of journal articles published in legal journals was conducted. To obtain a selection of European Law journals, we turned to the Washington & Lee Ranking (Law Journals: Submissions and Ranking, 2009-2016).25x https://managementtools4.wlu.edu/LawJournals (last accessed 8 October 2018). The original URL as it was used for this article is no longer available. It is, to our knowledge, the only ranking that exists that encompasses many law journals across the world and that indicates which journals are US-based, European-based etc. The ranking seems biased towards US journals,26xFor example, the prestigious Modern Law Review is ranked below the Stanford Journal of Animal Law and Policy (source: Washington and Lee Law Journals Ranking, https://managementtools4.wlu.edu/LawJournals, Combined score, Year 2017). Search conducted on 13 August 2018. but by filtering out those journals and by selecting the top-100 journals according to the 2016 ranking (n = 111),27xA number of journals ranked equal at rank 100. we expected our sample to include most of the important European-based journals. Indeed, highly respected journals such as Modern Law Review, European Law Review and Oxford Journal of Legal Studies appeared on the list.

Subsequently, all selected journals that were not EU-based (geographically), and journals whose titles indicated a non-European focus (e.g. African Journal of International and Comparative Law) were excluded from the list of journals to be studied, leaving a remainder of 84 journals. Of those journals, five were not accessible full-text to us and were consequently not examined. Additionally, one journal only provided ‘key points’, but no abstracts. Because it was unclear who produced the ‘key points’ and what they reflect (conclusions or also other information), this journal was not analysed. We decided to analyse all issues for the remaining 78 journals in the 2008-2017 period. Due to reasons of feasibility, the number of empirical and total articles were counted per issue, and later aggregated so that the data set included the number of empirical articles and the total number of articles per year and per journal per year.

Only research articles were inspected. Editorials, introductions, case notes, book reviews et cetera, were not included in the count. The strategy deployed to determine whether an article qualified as ‘empirical’, using the aforementioned guidelines, was to first look at the abstract. If there was any indication in the abstract that the article could contain empirical research, the full-text of the article was inspected. Articles that lacked an abstract were not inspected and excluded from the study.

Upon examination of the abstract, the starting point was to ascertain whether we recognised the described methodology as empirical. For example, abstracts that discussed conducting interviews, questionnaires or using statistics were assumed to fall within the definition of ELR and were only marginally checked. In comparison, articles that labelled their work ‘empirical’ or as a ‘case study’, were examined more thoroughly by inspecting the full-text version. To illustrate, we take the article by Jennifer Beard and Gregor Noll in the journal Social & Legal Studies on credibility and the sovereign of refugee status determination. The abstract describes that ‘[e]mpirically, the authors focus on the credibility assessment informing the refugee determination procedure operated by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees’. Although the authors describe their work as empirical, there is no evidence of data collection in terms of observation, survey or analysis of available data in the way described above. This article was therefore not counted as ‘empirical’.

The journals were coded by the authors, with each journal being analysed by one coder. Prior to the research, the coding scheme was constructed and tested by applying it to a number of issues, until the coders were under the impression that the agreement levels were high. The information on journal age (i.e. year of first publication) was collected from the websites of the various journals. Journal ranks were obtained from the Washington & Lee Ranking (after filtering out the non-European journals). The ranking is not perfect, yet intuitively correct, at least to an extent, as journals such as the Common Market Law Review and the German Law Journal are more prestigious than the International Journal of the Legal Profession and Arbitration in both the ranking as in the authors’ perception.

Each journal was coded independently by two coders in order to determine the area of law that the journals focus on (e.g. criminal justice) and to determine the journals being legal or extra-legal. The coding for both aforementioned variables was done based on the journal title (not based on its content or website description). Inter-coder reliability was moderate (legal/extra-legal; 75% agreement; Cohen’s k = .57, p < .001) to good (area of law; 89% agreement; Cohen’s k = .86, p < .001). The analyses controlled for these influences when testing a certain variable in order to rule out ‘noise’ from one or more of the variables.

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicates that the variable that measures the percentage of empirical articles does not follow a normal distribution [D(701) = .276, p < 0.001]. We nevertheless proceeded with conducting linear regression analysis, because ordinary least square regression analysis is robust for a violation of the normality assumption in case of a large sample size.

We first examined whether a rise of empirical articles can be observed in the 2008-2017 period. For this, we focused on the percentage of empirical articles per year, compared to the total number of articles. Percentages are preferred over the total number of empirical articles per year, since an increase in the number of empirical articles may have coincided with an increase of the total number of articles.

The percentages are reported in two ways. One method of calculation is to divide the total number of empirical articles per year by the total number of articles in a given year. The downside of this method of calculation is that journals or issues with a high number of articles (empirical and / or total) are overrepresented. To prevent this, one can calculate the percentage of empirical articles per year per journal, and subsequently take the average of journal percentages for each year. Table 1 reports the results of the two calculation methods.

Both calculation methods suggest no increase in the percentage of empirical articles over the years. The percentages fluctuate between 2008 and 2017, with both high and low peaks throughout the years. Focusing on the percentage empirical articles per year, the results reveal peaks (low) in 2012 and (high) in 2010 and 2017. When concentrating on the average of journal percentages, peaks (low) can be observed in 2015 and (high) 2011 and 2017.Table 1 Empirical Articles per Year, Frequencies and PercentagesYear Number of Articles Number of Empirical Articles Percentage Empirical Articles Average of Percentages Empirical Articles per Journal per Year 2008 1460 220 15.1 12.5 2009 1599 232 14.5 12.3 2010 1749 305 17.4 11.9 2011 1760 264 14.8 13.1 2012 1948 275 14.1 11.3 2013 1841 289 15.7 11.9 2014 1956 313 16.0 12.1 2015 2010 314 15.6 10.9 2016 2072 333 16.1 12.3 2017 2066 368 17.8 13.1 To explore whether the fluctuations are indeed random or coincidental, we conducted a regression analysis where we regressed the percentage empirical articles per journal (Percentage) on the year in which the articles were published (Publication Year). The results provide further support of no change of the percentage empirical articles over the years [R 2 = .00, F(1, 669) = .00, p = .98] (Table 2, Model 1). Similar results are obtained in a model that includes several other variables, including journal rank, the journal being legal or extra-legal, the year in which the journal published its first issue, and several areas of the law [b = .06, p = .79] (Table 2, Model 2).

Table 2 Regression Results of Effects of Predictors on the Percentage of Empirical ArticlesVariable (Model 1) Effect on Percentage (Model 2) Effect on Percentage (Model 3) Effect on Percentage Publication Year -.01 (.27) .06 (.23) .20* (.10) Year of First Publication -.08** (.03) Journal Rank -.05** (.02) Extra-Legal (ref. cat. Legal) 12.04*** (1.54) Area: Criminal Justice (ref. cat. Not Criminal Justice) 26.73*** (2.10) Area: International Law / Transnational Law / Fundamental Rights / Humanitarian / Comparative (ref. cat. Not International Law / Transnational Law / Fundamental Rights / Humanitarian / Comparative Law) 1.75 (1.94) Area: Constitutional Law (ref. cat. Not Constitutional Law) .43 (4.15) Area: European Law (ref. cat. Not European Law) -.85 (3.48) Area: Environmental (ref. cat. Not Environmental) 6.23* (2.79) Area: Business / Economic / Industry / IP (ref. cat. Other) 5.40** (1.92) Included Control Variables Journal NO NO YES N 701 701 701 R 2 .00 .31 .89 F .00 31.12 65.15 Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. Missing values are excluded. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

The overall results show no increase (or decrease), whereas this pattern might be different for individual journals. To test whether an increase (or decrease) could be observed on the journal level, we ran separate analyses for each journal individually.

Table 3 Regression Results of Effects of Year on the Percentage of Empirical Articles, per JournalVariable (1) International Review of Law and Economics (2) Regulation & Governance (3) Crime & Delinquency (4) Journal of International Criminal Justice (5) Journal of International Economic Law (6) European Company and Financial Law Review (7) The British Journal of Criminology (8) The International Journal of Human Rights Year 2.85 (1.04)* 4.71 (1.77)* .41 (.15)* -.45 (.15)* 1.47 (.59)* -1.15 (.44)* 2.20 (.46)** -1.11 (.48)† N 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 R 2 .48 .47 .50 .52 .44 .46 .74 .40 F 7.45 7.06 7.98 8.57 6.30 6.87 22.68 5.31 Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. Missing values are excluded. *p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001; † < .10. The International Journal of Human Rights revealed a significance score .05 after rounding, but higher than .05.

Focusing on statistically significant effects only, the results suggest that especially the journals Regulation & Governance, [b = 4.71, p = .03], the International Review of Law and Economics [b = 2.85, p = .03] and The British Journal of Criminology [b = 2.20, p < .01] saw an increase in empirical articles in the 2008-2017 period, and to a lesser extent Crime & Delinquency [b = .41, p < .02] and the Journal of International Economic Law [b = 1.47, p = .04]. In contrast, a decrease was observed for the Journal of International Criminal Justice [b = -.45, p = .02] and the European Company and Financial Law Review [b = -1.15, p = .03]. The International Journal of Human Rights also showed a decrease [b = -1.11, p = . 05], with the effect having a significance score of .05 after rounding (yet higher than .05).

As expected, journal characteristics also matter, as effects were observed for whether the journal was legal/extra-legal, the age of the journal (year of first publication), the area of the law and journal rank. When examining the effect of the journal being extra-legal or not on the percentage of empirical articles, it was found that, while controlling for other variables, the percentage of empirical articles is 12.0% [b = 12.04, p < .001] higher for extra-legal journals than for legal journals (Table 2, Model 2) (H1 confirmed). Descriptive statistics reveal that the average percentage of empirical articles per journal is 4.6% for legal journals, against 18.9% for extra-legal journals.

The area of the law also turned out to be an important predictor of the percentage of empirical articles published in a journal (Table 2, Model 2). Compared to journals ranked in the ‘other’ category (mostly ‘traditional’ law journals such as The Modern Law Review, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies and European Law Journal), journals in the field of criminal justice turn out to be 25% more likely to contain empirical articles than the ‘other’ journals [b = 26.73, p < .001] (controlling for other variables) (H2 confirmed). Additionally, journals dedicated to environmental issues [b = 6.23, p < .05] or that have a business / economic / industry / intellectual property focus [b = 5.40, p < .01] are more likely to contain empirical work (controlling for other variables).

A negative effect was found for journal age [b = -.08, p < .01] (Table 2, Model 2) (controlling for other variables), indicating that older journals are not more likely to publish empirical articles than journals that were established more recently (H3 confirmed). It should be noted that the coefficient is negative because in our data set more recent journals have a higher value (e.g. 2016) than older journals (e.g. 1980). Furthermore, higher-ranked journals (i.e. more prestigious journals) are associated with a higher percentage of empirical articles [b = -.05, p < .01] (more prestigious journals had lower values in the data set than less-prestigious journals), controlling for other variables (Table 2, Model 2) (H4 confirmed). Also here it should be noted that the coefficient is negative because in our data set a journal with a high value on the rank variable (e.g. 84) indicated that the journal was less prestigious than a journal with a lower value on the rank variable (e.g. 4).

Similar results were obtained when each variable was tested separately, except for journal rank (significant in the full model, not when tested separately), the variable that captures journals specialising in European Law (not significant in the full model, significant when tested separately) and the variable that captures whether the journal has a focus on environmental law (significant in the full model, not significant when tested separately). Additional analysis reveals a relationship between journal rank and whether a journal is legal or extra-legal (legal journals are ranked better than extra-legal journals): The effect of journal rank on the percentage of empirical articles depends on whether the journal is legal or extra-legal [b = .16, p < .001], which explains why journal rank is significant in the model that includes the legal/extra-legal variable, but not in a model without that variable. As to the European Law and environmental journals, the differences may be explained by their profile (legal/extra-legal, rank or year of first publication) or simply be the result of coincidence.

Furthermore, it may be that although the proportion of empirical articles has not increased over the years, the total number of empirical articles has. However, similar results were found when the total number of empirical articles is used as dependent variable instead of the proportion of empirical articles. Similar results were also obtained when excluding the journals that did reveal a statistically significant increase or decrease over time, however with the effect of journal age and journal rank becoming statistically insignificant. Apparently, the journals that were excluded filter out some of the age and rank effects.

Interaction effects between the year in which the articles were published on the one hand and the area of law covered by the journal, whether the journal is legal or extra-legal, the age of the journal and journal rank on the other hand were tested, but no statistically significant effects were found (H5-H8 not confirmed). The lack of interaction effects suggests that the relationship between the percentage of empirical articles and the year in which it was published is not different for legal journals compared to extra-legal journals, for journals that focus on a specific area of the law, for journals that are older compared to more recent journals, and for journals with a different rank. There is simply no increase of the percentage of empirical articles observed, also not for subcategories.

The only instance an increase in the 2008-2017 period is observed, is when the percentage of empirical articles is regressed on the journal (i.e. the name of the journal, represented in the data set by a unique number) and the year in which the articles were published. The results reveal a positive effect of the year in which the articles were published on the percentage of empirical articles (b = .20, p = .04) (Table 2, Model 3), suggesting a slight increase of the percentage of empirical articles over time (holding constant the journals in which the articles were published).

The relationship between the year and the percentage of empirical articles when controlling for the journals, taken together with the finding that older journals are more likely to publish empirical articles than more recent journals, raises the question in what other ways journals may differ, that is in what other ways than the ones already tested. Our data set did not provide us with any clues, nor could we identify other variables that we could collect that would explain this finding. Regardless, the effect sizes are small, meaning that the possible increase of the percentage of empirical articles is not substantial, even if the effect is not merely coincidence.

It is important to recognise the limitations when interpreting the empirical study we conducted. We cannot exclude possible selection bias resulting from the ranking that we used to include and exclude journals in the analysis. Furthermore, we only focus on journal articles in a specific period, not on other publications and / or in different periods. For example, a sample that would include empirical articles in the last 50 years could show a rise. As to publication type, it is not clear why other types of publications would show a different pattern than journal articles. Moreover, the articles were only further inspected for empirical research when an abstract gave rise to that. This means we removed false positives (false alarms, i.e. no empirical work after inspecting the full-text version), but not false negatives (empirical work in the articles that is overlooked because the abstract did not provide any cues for empirical work). Additionally, even though we controlled for journal rank in the analyses, the decision to not analyse journals where we had no access to the full-text creates possible selection bias as well, as we might only have full-text access to the ‘better’ journals (and those journals contain more empirical work). The journals that lacked full-text access had were ranked 21, 47, 58, 62, 79 and 95, respectively. -

5 Increasing the Use and Popularity of ELR

The results do not suggest an increase of the percentage of ELR articles in the 2008-2017 period that was researched. This begs the question as to why ELR is seemingly becoming more popular but not resulting in more empirical research. In the following, we discuss three important factors that are likely to impact the success of ELR: information, training and topic choice.28xThe following is based on the work of G. van Dijck, ‘Naar een succesformule voor empirisch-juridisch onderzoek’. 42 Justitiële Verkenningen 29 (2016). We concentrate on factors empirical legal researchers and the legal discipline have control over, since it is our belief that these factors are the easiest (or least difficult) to influence.

It should be noted that the popularity and use of ELR is also dependent on other important factors, the availability of research funds being an obvious one. However, the legal community exercises little control over funding, and the demand for more research funding is generally not effective. Furthermore, even though the interventions we discuss below will undoubtedly not have the exact same impact in different jurisdictions due to how law and legal research is perceived, organised and funded differently, we believe the interventions proposed below can be applied universally. We therefore mostly refrain from comparing whether or why interventions in Europe might work differently than in the US. Supposing we were to identify possible differences such as the legal academic community in the US being more competitive or the law being perceived as instrumental in the US in contrast to an autonomous system that contains values and experiences in Europe, these inferences would be mostly based on impressions and generalisations that may be unwarranted.5.1 Information

Empirical research presupposes the availability of data. Although data collection is part of the process of conducting empirical legal research, the existence of databases and a proper infrastructure can boost ELR, as the availability of data makes it more attractive (easier) to gather and subsequently analyse information. While data collection may not be an important problem for relatively small data sets, it is currently difficult in legal research to apply, for example, Big Data analytics due to the lack of an infrastructure that allows for such analysis.

The importance of the availability of data sets can be illustrated by means of network analysis. Network analysis, in a legal context, can be used as a citation analysis that allows testing how authoritative precedents are:29xJ.H. Fowler and others, ‘Network Analysis and the Law: Measuring the Legal Importance of Precedents at the U.S. Supreme Court’, 15 Political Analysis 324 (2007). decisions that are cited more frequently are presumed to be more important than decisions cited less frequently (qualitative data may also be used to conduct network analysis, but for the sake of the example we focus on citation networks). Network analysis studies have emerged in the legal field.30xR. Whalen, ‘Legal Networks: The Promises and Challenges of Legal Network Analysis’, 2 Michigan State Law Review 539 (2016), at 547ff (providing a brief overview of the development of network analysis in the legal domain). Network analysis, among other things, allows determining relevant sub-topics of a particular area of the law and identifying central precedents within the network or within a sub-topic.31xFor more information on network analysis, see van Dijck, MoneyLaw (and beyond).

In order to conduct network analysis, the data used to conduct this type of analysis need to be processed and made available in a certain (linked data) format so that computational analysis can be applied. This includes the automatic recognition of citations in order to prevent the researcher to have to manually go through all relevant cases (sometimes more than 10,000) and to have to write down all citations. Although legal information such as legislation and case law is readily available, it is not ready for network analysis or other types of computational analysis. However, data preparation for these types of analysis can be time-consuming for an individual researcher and may require technological knowledge that most legal researchers lack.

The network analysis example signals that without proper information it becomes difficult to conduct ELR. Consequently, the success of ELR will to a large extent depend on the information that is available or will be made available. Access to all case law and the publication of decisions of (dispute) commissions and disciplinary proceedings is a good start, but further action will be required, for example by making data sets accessible, regardless of whether they contain quantitative or qualitative data. Empirical legal researchers may want to go beyond accessibility, and think about reusability when composing a data set, that is composing data sets that may be used beyond the publications of the researcher who collected the data.

Of course, it will not be possible to capture all possibly relevant types of information. For instance, parties often intentionally opt for non-court solutions to ensure secrecy in alternative dispute resolution (ADR). However, even having some legal data sets (e.g. a case law database with certain variables) could already give a significant boost to ELR. Empirical legal researchers should therefore strive to not only conduct ELR, but also to build relevant data sets and infrastructures that allow for conducting ELR.

Additionally, researchers need not only to receive information - they also need to provide for it. They need to outline what can be expected of ELR in order to prevent creating false expectations. Empirical research, as any research, is incremental. For example, a single empirical study will most likely not determine whether the newly broadened right of victim’s to speak in court will have positive effects on the victim’s recovery and their satisfaction with the outcome. It can sometimes take many years of research before a clear answer is provided for a question. An example of this are the empirical studies on doctors and liability that have been conducted for decades, but only now making it apparent that the influence is more limited than feared.32xFor example, G. van Dijck, ‘Should Physicians Fear the Tort Claim? Reviewing Empirical Evidence’, 2015 JETL 282 (2015) (reviewing the evidence of the existence of defensive medicine). Nevertheless, the results may change as society changes and can result in the need for new research and consequently new outcomes. For instance, if doctors were no longer insured for damages claims, such claims might affect their behaviour to a greater extent. Consequently, not only does information need to be produced, the community of empirical legal researchers should provide information about what ELR can and cannot do.

ELR may therefore gain popularity if researchers would educate their peers in how to conduct and interpret empirical results. This particularly applies to ELR that relies on statistical analysis (e.g. regression analysis) of the collected data.33xMertz and Suchman, above n. 10, at 555-79. This type of empirical research, with its many numbers, coefficients and jargon, can be difficult to follow for legal scholars not trained in empirical research, and it may deter those scholars from conducting ELR themselves. The challenge here for empirical legal researchers is to conduct the research without losing sight of the fact that unskilled empiricists may also be interested in the results of the research, but that they may be discouraged by seemingly incomprehensible analyses. Only in this manner can ELR be introduced into the ‘mainstream’ of legal academics, where the community is composed of lawyers, judges and legislators who more often than not lack any empirical knowledge. This community therefore needs to be informed first of what ELR actually encompasses, and second, how the research results need to be interpreted. This informative element can take place through handbooks, reviews and websites that ideally would also provide for courses to develop and update ELR skills, but it can also be achieved in individual publications that explain the analyses for novices in an understandable way.5.2 Training

Training is evidently important. Without the necessary skills, it is impossible to properly conduct ELR. In practice, two main strategies can be observed for obtaining the necessary knowledge and skills to conduct ELR. One strategy is to rely on researchers from another discipline or on researchers who received training in empirical research methods in addition to legal training. The idea behind this strategy is straightforward: the involvement of empirically trained researchers will lead to more ELR.

That importing empirical knowledge leads to more ELR, is supported by a systematic review conducted in the Netherlands. Elbers investigated how many Ph.D. researchers who defended their thesis at a Dutch law faculty in 2015 have collected empirical data, what topic they investigated, which method they used and what background they have.34xN.A. Elbers, ‘Empirisch-juridisch onderzoek – toekomstmuziek of werkelijkheid?’, 6 Justitiële Verkenningen 43 (2016). She found that ELR is mostly conducted by those with a degree in another discipline than the law. The study reported that 33% of the PhD theses could be labelled as ELR, with the majority of the studies conducted by researchers who have a social science degree. Some of the (very few) lawyers collecting empirical data reportedly did not aim to conduct ELS according to themselves, even though their research questions could easily be qualified as empirical.

Following this import strategy, many US law faculties have tried to bridge the gap between the legal world and the empirical world by hiring researchers who have a legal diploma (JD) as well as a social science background (PhD). Even within the law faculties comprising 25% of the lowest ranked quartile of American law faculties, 11% of staff have completed a PhD in a different discipline than law.35xL.M. LoPucki, ‘Dawn of the Discipline-Based Law Faculty’, 65 Journal of Legal Education (2016). In 2016, LoPucki predicted that JD-PhD hiring in the US will continue to increase at its historical rate of 2.3% of faculty hired per year, and that by 2028 the proportion with that combined background will reach 50%.

LoPucki argues that the advantage of this development is that researchers will have experience in empirical research. The disadvantage, he claims, will be that they lack experience in the judicial profession, resulting in studies that are less interesting for the legal community. By hiring more researchers with a social sciences background, legally relevant questions may be ignored. This phenomenon is supported by recent research by LoPucki, who compared empirical legal studies conducted by legal scholars without a PhD in another discipline (referred to from here on out as: the Legal), with those with a PhD in another discipline (referred to from here on out as: the Legal+). His research demonstrates that the empirical research of the Legal focused more on judicial questions and judicial sources (such as case law), in comparison with the Legal+.36xL.M. LoPucki, ‘Disciplinary Legal Empiricism’, 76 Maryland Law Review (2017). The Legal also more frequently use existing data, whereas the Legal+ create new data sets, which LoPucki considers a sign of the Legal+ being unfamiliar with judicial information and how to use it. Finally, his research concluded that the Legal+, in comparison with the Legal, collaborates more frequently with other researchers who also have a PhD.

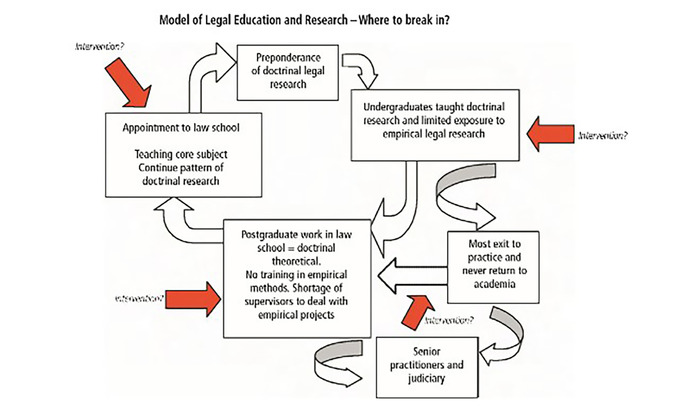

The second strategy is to teach empirical legal research skills from within, that is to have legally (doctrinally) trained scholars who enhance their knowledge and skills regarding ELR. This, however, is easier said than done. In 2004, the Nuffield Foundation funded a major inquiry into the UK’s capacity to carry out research on how law works in the real world. The central issue it sought to address was how the capacity to undertake empirical research in law could be expanded.37xNuffield Foundation, Nuffield Inquiry on Empirical Legal Research – Law in the Real World, 2004. Already then, the inquiry was initiated as a result of the widespread concern about a shortage of capacity to undertake empirical research in civil law and justice and that national demand for ELR could not be met within the current capacity. In order to handle the continuing ‘crisis in the capacity of UK universities to undertake empirical legal research’, the foundation provided recommendations, particularly in the area of legal scholarship culture in education. Recommendations included the funding of post-doctoral and special ELR fellowships, investment in interdisciplinary centres, enhancing the undergraduate curriculum to include more empirical content and the establishment of mid-career cross-disciplinary bursaries to encourage existing academics, from law or social sciences, to re-tool with specialist skills in ELR. Figure 1 demonstrates the difficulties associated with breaking the traditional structure of legal education in order to introduce ELR.Figure 1: Interventions to Promote ELR Source: Nuffield Foundation, Nuffield Inquiry on Empirical Legal Research – Law in the Real World, 2004, 30.

Source: Nuffield Foundation, Nuffield Inquiry on Empirical Legal Research – Law in the Real World, 2004, 30. Effective interventions to stimulate ELR are difficult to realise. Bar associations may set requirements that leave law faculties with little flexibility as to how to design their curricula. For example, in order to qualify as a Dutch lawyer, the Dutch Bar Association (Nederlandse Orde van Advocaten) has set out mandatory courses deemed to be the most important for a student’s legal education. Students are required to take courses in private law, civil procedure, substantive and procedural criminal law, government and administrative law.38x https://www.advocatenorde.nl/document/20160322-convenant-civiel-effect-1 (last accessed 8 October 2018). Most universities supplement these substantive courses with legal skills and method courses, such as academic writing, rather than with courses on ELR methods. In general, the curricula may be fixed and inflexible, leaving little room for courses on ELR. Most legal courses then do not incorporate ELR material into their teaching programmes, resulting in undergraduates having few opportunities to read ELR, much less develop their own skills in empirical data collection.39xCane and Kritzer, above n. 4. Additionally, law students’ perception may become that empirical legal studies is marginal and irrelevant.40x Ibid., 1039. The same applies to the post-graduate phase.

Furthermore, teachers rightfully teach what they are good at, which is often what they were taught themselves. Because teachers have little incentive to obtain ELR expertise, the self-replicating effect remains in full force. Without empirically trained teachers, ELR cannot be taught properly. The lack of widely accessible and appealing literature also does not help in overcoming the lack of expertise.41xThe first law school textbook intended specifically for courses on ELR, R.M. Lawless, J.K. Robbennolt and T.S. Ulen, Empirical Methods in Law, Wolters Kluwer, Law and Business 2009, appeared only in late 2009.

Even if the decision was made to include ELR methods as a course in the curriculum, there may still be a problem with the student expectations. Already at the beginning of their study, students have their own expectations of what law school will entail, and those expectations do not necessarily match with what the law school sees as its mission.42xCane and Kritzer, above n. 4. Given the media and the history of legal education, most students are likely to enter university with the belief that it will be a very dogmatic, text based education focusing on the analysis of words.43x Ibid. The farther removed a methods course is from this expectation, the more reluctant and less engaged students may be to participate in it. It is thus harder to justify spending time on a course that students will, in their opinion, seldom use in their future career.

From the above it becomes clear that the embedding of ELR in law schools requires some top-down steering from the administrators to intervene in the self-replicating cycle. One solution is to simply incorporate ELR courses or elements in existing courses, but more creative solutions exist as well. For example, funding schemes may be designed that require applicants to collaborate with other faculties or to provide for training and workshops in addition to research output.5.3 Topic Choice

If ELR is to be recognised as relevant, selecting proper research topics is essential. In order for the legal community – scholars and practitioners – to understand the relevance of conducting empirical studies, ELR needs to somehow relate to what ‘the’ legal community considers a legal problem.

The question of what is considered a legal problem does not have straightforward answer. Convincing evidence on the matter is lacking, and the legal community may simply be too diverse to provide a simple answer to the question. What is perceived to be legally relevant may depend on the community in terms of geography (i.e. country, jurisdiction), time and the type of community (e.g. practitioners, doctrinal scholars, empirical legal scholars). What is considered ‘legal’ to one can be seen as ‘extra-legal’ or ‘non-legal’ to another. For example, ELR in the US is to an important extent conducted by economists, political scientists and psychologists.44xMertz and Suchman, above n. 10, at 555. The variety of the tools and methods used in the research can vary considerably. To make some generalisations: the economists use financial econometric tools to answer questions of corporate law, the political scientists test game theory models of court decision making, and the psychologists conduct experiments on negotiation, courtroom perception and juries. Researchers from another discipline than the legal discipline may ask questions that are of limited relevance to ‘the’ legal community, they may be interested in other aspects than legal scholars or legal practitioners, or they may overlook legal nuances, allowing the legal community to dismiss the research as being ‘non-legal’.

The discrepancy between the researched topic, and the corresponding legal reality is evidenced by publications in ‘flagship journals’ such as JELS and LSR. For some studies, it may be asked what value society, and in particular the legal realm, can obtain from such research. What can a legal practitioner learn from the analysis of kinship and its relationship with the protection of private property in China, or from research on how activists in Myanmar have ensured greater attention to minority groups in the country? The direct relevance of these studies seems minimal, at least to legal practitioners. This does not mean that the research is useless. In fact, many of these studies combined can lead to a better understanding of how fundamental rights can be enforced. However, if these types of studies constitute mainstream ELR studies, the research will only ever be read marginally, as many in the legal community will not relate to the issue that was researched, particularly in legal communities that have a rather doctrinal or normative focus. Consequently, ELR needs, at least in part, to focus on topics that other legal researchers (and perhaps practitioners) are interested in. Regardless of whether the legal discipline is perceived as doctrinal, normative, instrumental et cetera, there will always be a need to know how the law works, what its effects are, and what impact a new or reformed rule may have. It is then that ELR may enhance legal analysis by providing empirical input reasoning, by testing assumptions, or by evaluating reforms.

Nevertheless, it can sometimes be advisable not to engage in ELR that is doctrinally relevant. Following a case where a married woman brought her partner to court when she fell out of a hammock placed in their private garden and suffered damage, the doctrinally relevant question may arise if the granting of such claims results in a premium increase of liability insurance.45xDutch Supreme Court 8 October 2010, ECLI:NL:HR:2010:BM6095. While this is an empirical question that is arguably relevant for evaluating the decision, answering the question is time-consuming and complex in comparison to the knowledge to be gained. Is the answer important enough to spend years of ELR studying it? In selecting the topic, consideration should be given to all of these factors. A balancing act must therefore be done between the expected costs and the expected benefits. -

6 Conclusion

The empirical results reveal the following:

An increase was only found for a small number of journals, with a small number of other journals showing a decrease over time. Overall, there is no increase of the proportion of empirical articles over the 2008-2017 period.

The percentage of empirical articles is higher for extra-legal journals than for legal journals. The average proportion of empirical articles per journal is 4.6% for legal journals, against 18.9% for extra-legal journals, with the former percentage showing resemblance with similar research conducted in the US.46xDiamond and Mueller, above n. 7, at 581, 587 (reporting 5.7% for US law review articles).

Criminal justice journals, environmental journals and economically oriented journals are more likely to publish empirical articles than other journals.

Higher-ranked journals (i.e. more prestigious journals) are more likely to publish empirical articles than lower-ranked journals.

Older journals are more likely to publish empirical work than younger journals, but not at an increasing rate.

A journal being legal/extra-legal, a journal in a specific field, the rank of the journal, or the age of the journal does not make it more (or less) likely that the journal will publish empirical articles at an increasing (or decreasing) rate.

The claim that the proportion of empirical articles has increased over the years is doubtful at best. In order to increase the proportion of ELR in publication outlets, three factors relevant to the success of ELR were discussed: topic choice, information and training. For interest in empirical legal studies to surge, the research needs to be seen as relevant for the legal community, and needs to be made understandable, for practitioners and scholars alike, including those with a limited background in the area. The acceptance and popularity of ELR is thereby not limited to enlightening and training legal scholars, but also extends to knowing how to select the appropriate topic and to building databases or data sets that legal scholars can use.

-

Appendix: Journal List

Journal Rank European Journal of International law 2 Journal of Competition Law and Economics 3 German Law Journal 4 Journal of International Criminal Justice 5 International Journal of Constitutional Law 6 Journal of International Economic Law 7 International and Comparative Law Quarterly 11 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 12 Human Rights Law Review 13 Leiden Journal of International Law 14 Common Market Law Review 15 Journal of International Dispute Settlement 15 International Review of Law and Economics 17 International Review of the Red Cross 17 Regulation & Governance 19 (Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law) 21 Modern Law Review 23 Journal of Conflict and Security Law 26 Law and Philosophy 27 European Law Review 29 International Criminal Law Review 29 International Journal of Law & Information Technology 29 European Law Journal 35 Journal of Law and Society 35 Climate Law 38 Journal of Environmental Law 38 Law, Probability and Risk 38 Criminal Law and Philosophy 42 British Journal of Criminology 43 Carbon & Climate Law Review 43 International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 43 Transnational Environmental Law 43 European Business Organization Law Review 47 European Journal of Risk Regulation 47 Journal of Criminal Justice 47 (Journal of Private International Law) 47 Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 51 International Journal of Refugee Law 51 Crime & Delinquency 53 European Constitutional Law Review 53 Transnational Legal Theory 53 Utrecht Law Review 53 Arbitration International 58 Cambridge Law Journal 58 (Journal of Corporate Law Studies) 58 Business and Human Rights Journal 62 (Capital Markets Law Journal) 62 Erasmus Law Review 62 International Journal of Transitional Justice 62 Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law (only accessible from 2008-2013) 62 Law Quarterly Review 62 Oxford Journal of Law and Religion 62 Criminal Law Forum 70 International Organizations Law Review 70 Journal of World Intellectual Property 70 Netherlands Yearbook of International Law 70 Nordic Journal of International Law 70 Ratio Juris: An International Journal of Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law 70 World Trade Review 70 (Business Law International) 79 Crime, Law and Social Change 79 Current Legal Problems 79 European Competition Journal 79 European Intellectual Property Review 79 Industrial Law Journal 79 International Journal of the Legal Profession 79 International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law 79 Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 79 Journal of World Investment & Trade 79 Legal Ethics 79 SCRIPTed: a Journal of Law, Technology & Society 79 Amsterdam Law Forum 95 Civil Justice Quarterly 95 Computer Law and Security Review 95 European Company and Financial Law Review 95 European Human Rights Law Review 95 European Journal of Law and Economics 95 International Journal of Human Rights 95 (Journal of Comparative Law) 95 Journal of Human Rights 95 Journal of World Energy Law & Business 95 Jurisprudence: An International Journal of Legal and Political Thought 95 Punishment & Society 95 Social & Legal Studies 95 Note: Titles between brackets indicate journals that were not analysed.

- * The data set is available for scientific purposes upon request.

-

1 H.M. Kritzer, ‘Empirical Legal Studies Before 1940: A Bibliographic Essay’, 6 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (2009), at 926.

-

2 www.lawandsociety.org/history.html (last accessed 8 October 2018).

-

3 M. Heise, ‘The Past, Present, And Future of Empirical Legal Scholarship: Judicial Decision Making and the New Empiricism’, University of Illinois Law Review (2002), at 819; R.H. McAdams and T.S. Ulen, ‘Introduction to the Symposium on Empirical and Experimental Methods in Law’, University of Illinois Law Review (2002).

-

4 P. Cane and H.M. Kritzer, The Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Research (2010), at 1026.

-

5 L.A. Gordon, The Empiricists: Legal Scholars at the Forefront of Data-Based Research (2010).

-

6 M. Heise, ‘An Analysis of Empirical Legal Scholarship Production, 1990-2009’, 2011 University of Illinois Law Review (2011), at 1739. See also R.C. Ellickson, ‘Trends in Legal Scholarship: a Statistical Study’, 81 Journal of Legal Studies (2000) 517, at 528-29 (researching the 1982-1996 period and finding that ‘[t]he indexes for both empiric! and quantitate! (…) are virtually flat from 1982 to 1996 (…) [but that] the indexes for both statistic! Significan! And Table 1 almost double over the same time frame’, which suggests that ‘law professors and students have become more inclined to produce (although not consume) quantitative analysis’) and T.E. George, ‘An Empirical Study of Empirical Legal Scholarship: The Top Law Schools’, 81 Indiana Law Journal (2006) 141, at 147 (extending the Ellickson study to the 1994-2004 period), both researching the number of references to empirical legal scholarship.

-

7 S.S. Diamond and P. Mueller, ‘Empirical Legal Scholarship in Law Reviews’, 6 Annual Review of Law and Social Science (2010) 581, at 581, 587 (reporting that 5.7% of the US law review articles contain original empirical data, with original defined as data collected by the researcher himself or herself).

-

8 Ibid., 581, 587. See also Heise, ‘The Past, Present, And Future of Empirical Legal Scholarship: Judicial Decision Making and the New Empiricism’; McAdams and Ulen, ‘Introduction to the Symposium on Empirical and Experimental Methods in Law’. For examples of ELS research from before 1940, see Kritzer, ‘Empirical Legal Studies Before 1940: A Bibliographic Essay’.

-

9 www.lawandsociety.org/history.html (last accessed 8 October 2018).

-

10 E. Mertz and M.C. Suchman, ‘A New Legal Empiricism? Assessing ELS and NLR’, 6 Annual Review of Law and Social Science (2010), at 555.

-

11 T. Eisenberg, ‘Why Do Empirical Legal Scholarship?’, 41 San Diego Law Review (2002) 1741, 1741.

-

12 See, for example, L. Epstein and G. King, ‘The Rules of Inference’, 69 University of Chicago Law Review 1 (2002).

-

13 M. Heise, ‘The Importance of Being Empirical’, 26 Pepp L Rev (1999) 807, 812.

-

14 R. van Gestel and H.-W. Micklitz, ‘Revitalizing Doctrinal Legal Research in Europe: What About Methodology?’, EUI LAW 2011/05 (2011), at 2.

-

15 X.E. Kramer, ‘Editorial: Empirical Legal Studies in Private International Law’, Nederlands Internationaal Privaatrecht (2) (2015), at 195.

-

16 Cane and Kritzer, above n. 4; L. Epstein and A.D. Martin, An Introduction to Empirical Legal Research (Oxford University Press 2014).

-

17 http://noleslaw.net (last accessed 8 October 2018).

-

18 R. Korobkin, ‘Empirical Scholarship in Contract Law: Possibilities and Pitfalls’, University of Illinois Law Review 1033, (2002) at 1035 (fn 3).

-

19 Diamond and Mueller, above n. 7; C.E. Schneider and L.E. Teitelbaum, ‘Life’s Golden Tree: Empirical Scholarship and American Law’, Utah Law Review (2006), at 53; S.S. Diamond, ‘Empirical Marine Life in Legal Waters: Clams, Dolphins, and Plankton’, Univ Ill Law Rev (2002) at 803, 805.

-

20 ‘Should’ according to, for example, certain respondents or interviewees.

-

21 See http://acle.uva.nl/content/events/conferences/2016/06/conference-on-empirical-legal-studies-2016---21-and-22-june-2016.html (last accessed 8 October 2018).

-

22 For example, Heise, ‘The Importance of Being Empirical’, 810-11; C.A. Nard, ‘Empirical Legal Scholarship: Reestablishing a Dialogue Between the Academy and the Profession’, 30 Wake Forest Law Review (1995), at 348-61.

-

23 J.K. Gionfriddo, ‘Thinking Like a Laywer: The Heuristics of Case Synthesis’, 40 Texas Tech Law Review 1 (2007) (defining case synthesis in fn 1).

-

24 Ibid., 31.

-

25 https://managementtools4.wlu.edu/LawJournals (last accessed 8 October 2018). The original URL as it was used for this article is no longer available.

-

26 For example, the prestigious Modern Law Review is ranked below the Stanford Journal of Animal Law and Policy (source: Washington and Lee Law Journals Ranking, https://managementtools4.wlu.edu/LawJournals, Combined score, Year 2017). Search conducted on 13 August 2018.

-

27 A number of journals ranked equal at rank 100.

-

28 The following is based on the work of G. van Dijck, ‘Naar een succesformule voor empirisch-juridisch onderzoek’. 42 Justitiële Verkenningen 29 (2016).

-

29 J.H. Fowler and others, ‘Network Analysis and the Law: Measuring the Legal Importance of Precedents at the U.S. Supreme Court’, 15 Political Analysis 324 (2007).

-

30 R. Whalen, ‘Legal Networks: The Promises and Challenges of Legal Network Analysis’, 2 Michigan State Law Review 539 (2016), at 547ff (providing a brief overview of the development of network analysis in the legal domain).

-

31 For more information on network analysis, see van Dijck, MoneyLaw (and beyond).

-

32 For example, G. van Dijck, ‘Should Physicians Fear the Tort Claim? Reviewing Empirical Evidence’, 2015 JETL 282 (2015) (reviewing the evidence of the existence of defensive medicine).

-

33 Mertz and Suchman, above n. 10, at 555-79.

-

34 N.A. Elbers, ‘Empirisch-juridisch onderzoek – toekomstmuziek of werkelijkheid?’, 6 Justitiële Verkenningen 43 (2016).

-

35 L.M. LoPucki, ‘Dawn of the Discipline-Based Law Faculty’, 65 Journal of Legal Education (2016).

-

36 L.M. LoPucki, ‘Disciplinary Legal Empiricism’, 76 Maryland Law Review (2017).

-

37 Nuffield Foundation, Nuffield Inquiry on Empirical Legal Research – Law in the Real World, 2004.

-

38 https://www.advocatenorde.nl/document/20160322-convenant-civiel-effect-1 (last accessed 8 October 2018).

-

39 Cane and Kritzer, above n. 4.

-

40 Ibid., 1039.

-

41 The first law school textbook intended specifically for courses on ELR, R.M. Lawless, J.K. Robbennolt and T.S. Ulen, Empirical Methods in Law, Wolters Kluwer, Law and Business 2009, appeared only in late 2009.

-

42 Cane and Kritzer, above n. 4.

-

43 Ibid.

-

44 Mertz and Suchman, above n. 10, at 555.

-

45 Dutch Supreme Court 8 October 2010, ECLI:NL:HR:2010:BM6095.

-

46 Diamond and Mueller, above n. 7, at 581, 587 (reporting 5.7% for US law review articles).

Erasmus Law Review |

|

| Article | Empirical Legal Research in Europe: Prevalence, Obstacles, and Interventions |

| Keywords | empirical legal research, Europe, popularity, increase, journals |

| Authors | Gijs van Dijck, Shahar Sverdlov en Gabriela Buck * xThe data set is available for scientific purposes upon request. |

| DOI | 10.5553/ELR.000107 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Gijs van Dijck, Shahar Sverdlov and Gabriela Buck, "Empirical Legal Research in Europe: Prevalence, Obstacles, and Interventions", Erasmus Law Review, 2, (2018):105-119

Empirical Legal research (ELR) has become well established in the United States, whereas its popularity in Europe is debatable. This article explores the popularity of ELR in Europe. The authors carried out an empirical analysis of 78 European-based law journals, encompassing issues from 2008-2017. The findings demonstrate that a supposed increase of ELR is questionable (at best). |