-

1 Introduction

On 7 May 1975 President Ford signed the executive order1x Executive Order 11858, 40 FR 20263 (7 May 1975), www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/11858.html. that established the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). Pursuant to Sec. 1(b)(3), the main responsibility of CFIUS is to monitor the impact of both foreign direct investments (FDI) and foreign portfolio investments in the United States and to review investments that might adversely affect national interests. CFIUS is thus concerned with the screening of inbound FDI, i.e. an investment made by foreign investors into undertakings in the United States. It seems, however, that after almost half a century, CFIUS will get a counterpart. As a result of the Covid-19 crisis and the geopolitical rivalry with China, voices have been raised in recent years in the United States to screen outbound FDI too; i.e. FDI by US investors into undertakings that are established in foreign countries. Accordingly, on 26 May 2021 Senators Bob Casey and John Cornyn introduced the bipartisan National Critical Capabilities and Defence Act (NCCDA).2x The National Critical Capabilities Act is accessible via Text S.1854, 117th Congress (2021-2022): National Critical Capabilities Defense Act of 2021, Congress.gov, Library of Congress, www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6329/text. The NCCDA aims at establishing an inter-agency committee (the Committee on National Critical Capabilities; CNCC) to review outbound FDI.

The NCCDA proposal fits within a broader tendency of increased protectionism and FDI scrutiny. Owing to its benefits for companies, customers and countries,3x L.E. Trakman and N.W. Ranieri, ‘Foreign Direct Investment: An Overview’, in L.E. Trakman and N.W. Ranieri (eds.), Regionalism in International Investment Law (2013) 1, at 1. states were competing to attract FDI for quite a long period.4x Y.S. Lee, ‘Foreign Direct Investment and Regional Trade Liberalization: A Viable Answer for Economic Development?’ 39 Journal of World Trade 701, at 702 (2005). See for the history of FDI: Trakman and Ranieri, above n. 3, at 15-26. In recent years, however, the liberalisation of FDI is increasingly being questioned and restricted. This is evidenced, among other things, by an increasing number of states putting in place FDI screenings mechanisms. With the adoption of Regulation 2019/452,5x Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council 2019/452, OJ L 791/1. the EU and its Member States have joined the ranks of these countries. Most of these screening mechanisms so far, however, are meant to address the risks associated with inward FDI. Article 1(2) Regulation 2019/452, for instance, states that the Regulation creates a framework for the screening of FDI into the Union. This wording is also used by Recital 3, which goes on to add that ‘[o]utward investment and access to third country markets are dealt with under other trade and investment policies’.

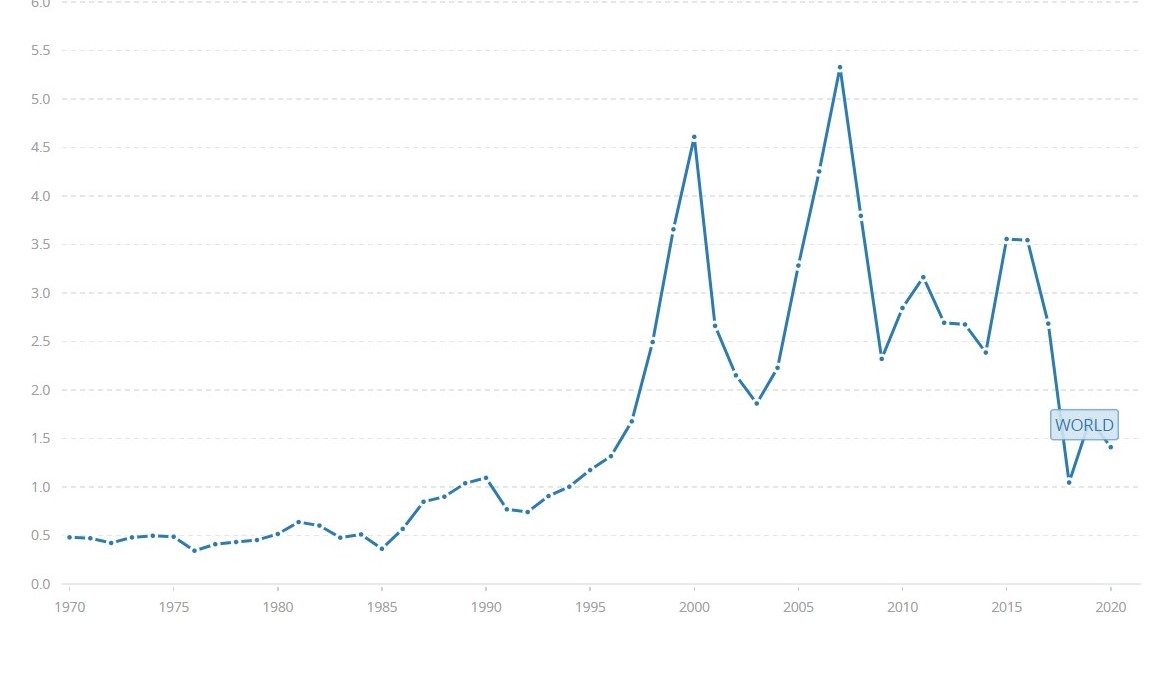

Considering these recent developments, the question arises whether the EU and its Members States should also screen outbound FDI and, if so, what inspirationFDI Net Inflows as % of GDP

can be drawn, if any, from the NCCDA. In order to address these issues, the next paragraph will first of all set the scene and pay attention to the changed attitude towards FDI. Paragraph 3 will focus on the first part of the question, i.e. whether it is necessary for the EU and its Member States to screen outbound FDI. Then, in paragraph 4 the NCCDA will be discussed. In paragraph 5 the second part of the question, namely, what inspiration can be drawn from the NCCDA, will be addressed. Finally, paragraph 6 will contain the conclusion.

-

2 The Changed Attitude towards FDI

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the end of the Cold War, the adoption of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the world entered a new era of ‘true economic liberalism’ and (hyper) economic globalisation in the 1990s.6x K.C. Cai, The Politics of Economic Regionalism. Explaining Regional Economic Integration in East Asia (2010), at 57-67. See with regard to the globalisation of the economic order: D. Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of World Economy (2011). Globalisation has multiple facets, but economic globalisation can be described as ‘the gradual integration of national economies into one borderless global economy [and] [i]t encompasses both (free) international trade and (unrestricted) foreign direct investments’.7x P. Van Den Bossche, The Law and Policy of the World Trade Organization. Text, Cases and Materials (2005), at 3. Globalisation contributed greatly to the liberalisation of FDI. In order to regulate and promote the liberalisation of FDI, multilateral institutions, such as the WTO, and international rules and norms, such as the most-favoured -nation and national treatment clauses, were created. The international rules and norms disciplined states by discouraging them from taking investment restrictive measures. Moreover, those rules and norms offered a certain degree of legal certainty and predictability for investors and traders.8x Ibid., at 36. Hence, owing to the creation of the WTO and the adoption of international rules and norms regulating and promoting the liberalisation of FDI, the international economic order became more open and more rules based, consequently exerting a positive effect on FDI flows. Figure 19x The figure is taken from the website of the World Bank, www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?end=2020&start=1970&view=chart. See also: UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2021: Investing in sustainable recovery (2021), www.unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf#page=20; OECD, FDI in figures: April 2022, www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/FDI-in-Figures-April-2022.pdf. illustrates this well. From the early 1990s to the 2000s the FDI net inflows as a percentage of the GDP have increased tremendously (+270%) as compared with the preceding years.

Illustrative of this positive approach towards FDI is also the communication of the European Commission (Commission) with regard to a European international investment policy. In that communication, the Commission noted that ‘… the benefits of inward FDI into the EU are well-established … [and that] this explains why our Member States, like other nations around the world, make significant efforts to attract foreign investment’.10x European Commission, Towards a comprehensive European international investment policy (7 July 2010), COM(2010)343 final, at 3. With regard to outbound FDI, the Commission noted that ‘… outward investment makes a positive and significant contribution to the competitiveness of European enterprises, notably in the form of higher productivity’.11x Ibid.

However, from 2017 onwards the positive attitude towards FDI changed, and this resulted in a significant drop in FDI transactions in 2018, as is clear from Figure 1.12x From 1970 until 2020, there were a couple of significant drops in FDI transactions. The first one was in 2003, which can be attributed to the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan and the subsequent war on terrorism. The second significant drop was in 2009, which was the consequence of the 2008 financial crises. In 2014, FDI transactions again fell significantly as a consequence of the global 2012/2013 financial crisis. The reason for this change can be traced back to the series of Chinese takeovers, in 2016, of EU companies with key technologies. In line with ‘Made in China 2025’, Chinese investors, often backed up by the Chinese government, aimed at taking over EU companies possessing technological knowledge in order to upgrade China’s industry.13x See for instance J. Wübbeke et al., ‘Made in China 2025: The Making of High-tech Superpower and Consequences for Industrial Countries’ (2016), at 52, www.merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Made%20in%20China%202025.pdf.

As a consequence of those takeovers, the German, French and Italian governments sent, in February 2017, a letter to the Commission expressing their concerns about the EU investment policy.14x Letter of German, French and Italian governments to Commissioner Malmström (February 2017), www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/S-T/schreiben-de-fr-it-an-malmstroem.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5. The concerns of these Member States were twofold: on the one hand, they noted a lack of reciprocity, while, on the other, they feared that European crown jewels in the tech industry would fall into foreign hands. The lack of reciprocity concerns an incongruity in rights: EU investors do not have the same rights in third countries as the investors from those third countries have in the EU. This incongruity manifests itself in several ways. For example, third countries deny EU investors access to (certain sectors of) the economy. And when EU investors do gain access, they often have to operate under more unfavourable conditions than national investors, who are often supported through subsidies. In addition to a lack of reciprocity, they voiced their concerns about ‘a possible sell-out of European expertise’.15x Ibid. In its reflection paper on harnessing globalisation, the Commission acknowledged the concerns of the Member States with regard to ‘…foreign investors, notably state-owned enterprises, taking over European companies with key technologies for strategic reasons’.16x European Commission, Reflection paper on harnessing globalization (10 May 2017), COM(2017)240 final, at 18. In order to address these concerns, Regulation 2019/452 was adopted in March 2019. In the United States, a more or less similar process took place. Owing to Chinese FDI, concerns were also voiced in the United States, resulting in the adoption of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) in mid-2018.17x See inter alia: P. Corcoran, ‘Investing in Security: CFIUS and China after FIRRMA’, 52 New York University Journal of International Law and Politics (2019), at 7-14 and P. Rose, ‘FIRRMA and National Insecurity’, Ohio State Public Law Working Paper 2018:452, at 8-11. The EU and the United States are, however, not the only ones that have adopted legislation to screen FDI. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has noticed that in recent years, more and more states are adjusting existing FDI screening mechanisms and adopting new policies in order to safeguard their national interests.18x OECD, Research Note on Current and Emerging Trends: Acquisition- and Ownership- Related Policies to Safeguard Essential Security Interests. New Policies to Manage New Threats (12 March 2019), at 4. -

3 To Screen or Not to Screen, That Is the Question

As stated previously, the Covid-19 crisis and the geopolitical rivalry with China are the main drivers behind the NCCDA proposal. These developments beg the question of whether the EU should also screen outbound FDI. There are at least four reasons why the EU and its Member States should consider the screening of outbound FDI.

First, it is necessary to prevent undesirable knowledge transfer. One of the main underlying motives of the Regulation 2019/452 is to prevent EU companies with high-quality technological knowledge from falling into foreign hands. The assumption is that the involvement of foreign investors, who are directly or indirectly under the influence of a foreign government, could potentially endanger the security and/or public order of the EU and its Member States. Foreign investors, and thus foreign governments, may gain access to strategic and sensitive knowledge through FDI in the form of a takeover, for instance, and then use it for geopolitical purposes. This is the case, for example, when a foreign investor acquires a stake in the Urenco group, which is engaged in enriching uranium. By acquiring a stake in Urenco that qualifies as FDI, foreign governments can gain access to Urenco’s knowledge and expertise through the investors. This is especially true of countries that have state-driven planned economies where the distinction between market and government is difficult to make. Furthermore, the involvement of foreign investors, and thus foreign governments, may jeopardise the continuity of the supply, service and production of vital services and goods.19x See inter alia: W.E. Veiligheid, Tussen naïviteit en paranoia: Nationale veiligheidsbelangen bij buitenlandse overnames en investeringen in vitale sectoren (2014); Kamerstukken II 2015/16, 30 821, nr. 27, at 2 and C.D.J. Bulten, B.J. de Jong & E.J. Breuking, Vitale vennootschappen in veilige handen (2017), at 142.

Regulation 2019/452 only partially addresses this problem, however, since Member States can only screen inbound FDI. So if a Chinese investor wants to acquire a majority stake in Urenco, Member States can screen and eventually block the transaction. However, foreign governments can also gain access to strategic and sensitive knowledge through outbound FDI where an EU company decides to enter the market of a third, non-EU country. China’s policy is illustrative in this regard. The Chinese government is trying in many ways to get a grip on foreign companies in order to gain access to strategic and sensitive knowledge. In order to get access to the Chinese market, EU companies are often forced to create joint ventures with local companies.20x European Commission, EU-China A strategic outlook’ (12 March 2019), JOIN(2019)5 final, at 6. The EU-China Joint Venture Radar of Datenna reveals that of the top-500 largest EU joint ventures in China, 32% are under the significant influence of the Chinese government. Of this 32%, the influence of the Chinese government in ninety-nine joint ventures is high, meaning that the Chinese government is the controlling shareholder of the Chinese company party to the joint venture. This in turn means that the Chinese government is the controlling shareholder, through the Chinese company, of the joint venture to which EU companies are party. Furthermore, the EU-China Joint Venture Radar reveals that in 71% of the cases, EU parties to joint ventures hold less than 50% of the shares in the joint ventures, while in 35% of all the EU-Chinese joint ventures, EU companies possess one-third or less of the shareholdings in the joint ventures.21x The EU-China Joint Ventures Radar of Datenna, www.datenna.com/china-eu-joint-venture-radar. Datenna has also created an US-China Joint Ventures Rader, www.datenna.com/us-china-joint-venture-radar. Moreover, EU companies are often forced to transfer key technologies to Chinese companies in order to get access to the Chinese market.22x European Commission (March 2019), above n. 20. Finally, a recent law amendment seeks to give Communist party officials, known as party cells, more influence over the corporate governance and strategy setting of foreign companies.23x D. Kwoken en Sam Goodman, ‘Chinese Communist Cells in Western Firms? Xi Jinping Has Pressed for Measures Giving Party Apparatchiks More Power over Foreign Companies’, Wallstreet Journal (11 July 2022), www.wsj.com/articles/communist-cells-in-western-firms-business-investment-returns-xi-jinping-11657552354. See also: J. Doyon, ‘Influence without Ownership: The Chinese Communist Party Targets the Private Sector’, Institut Montaigne (23 January 2021), www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/influence-without-ownership-chinese-communist-party-targets-private-sector. Since there is currently no legal framework at the EU level for screening outbound FDI, it is quite conceivable that third EU countries might change strategies by giving additional incentives to outbound FDI and thus acquire strategic and sensitive knowledge. Screening of outbound FDI is thus necessary in order to fill the gap.

In 2021, the EU adopted Regulation 2021/821,24x Regulation (EU) 2021/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council of May 2021, setting up a Union regime for the export, brokering, technical assistance, transit and transfer of dual-use items, OJ L 206/I. which governs the export control regime of dual-use items.25x The Court employs the term dual-use goods while Regulation 2021/821 uses the term dual-use items. For convenience, the term ‘dual-use items’ will henceforth be used, thereby assuming that it is a synonym for dual-use goods. What, then, would be the added value of screening outbound FDI if restrictive measures related to dual-use items already fall within the ambit of Regulation 2021/821?26x The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for raising this question. While an extensive discussion of Regulation 2021/821 and the EU export control regime of dual-use items is outside the scope of the present article, it is helpful to recall the definition of dual-use items. Pursuant to Article 2(1) Regulation 2021/821, dual-use items mean items, including software and technology, that can be used for both civil and military purposes and include items that can be used for the design, development, production or use of nuclear, chemical or biological weapons or their means of delivery. As is clear from this definition, dual-use items, first of all, have, besides a civilian purpose, also a military component. Secondly, the definition employed by Article 2(1) Regulation 2021/821 indicates that dual-use items must be capable of being used in the design, development, production or means of delivery of weapons. Accordingly, items that are unrelated to weapons or items that cannot be used for military purposes cannot be qualified as dual-use items and thus do not fall within the scope of Regulation 2021/821 even though such items might be of strategic importance. Think, for instance, about the services delivered by Centric,27x www.centric.eu/en/. a leading Dutch company active in the IT sector. Centric delivers IT services not only to other businesses but also to the Dutch Central Bank (De Nederlandsche Bank)28x www.centric.eu/en/news/centric-helps-dnb-increase-it-flexibility-and-performance/. and many Dutch municipalities. Suppose now that Centric decides to set up a joint venture with a Chinese company in China, whereby the joint venture will provide workspace services to businesses. Such a transaction in itself is not problematic, and the services provided by the joint venture cannot be qualified as dual-use items, owing to which it will not fall within the scope of Regulation 2021/821. However, considering that Centric also provides services to the Dutch Central Bank and many Dutch municipalities, it is important to screen its outbound investments in order to secure the strategic interests of the Netherlands. This is especially the case if Centric would enter into a joint venture with a Chinese company that is state-owned or where the Chinese government is (indirectly) the controlling shareholder and whereby Centric holds minority shareholdings in the joint venture. So the screening of outbound FDI is meant not only to prevent the undesirable transfer of key technologies but, more broadly, to prevent the transfer of all sensitive knowledge and information that can be used for geopolitical purposes.

Second, the EU must protect its economic, and therefore political, independence. Owing to globalisation and investment liberalisation, global economies have become increasingly interdependent. Economic interdependence was long considered as a blessing since it forced countries to settle their conflicts and disputes peacefully. In fact, the rationale behind the European integration project was economic interdependence. However, economic interdependence nowadays is something undesirable and avoidable since investment and trade policies are increasingly used as tools pure for geopolitical and strategic purposes.29x See inter alia: N. Zamani, ‘The Economization and Politization of International Economic Law: Toward a Geo-Economic Legal Order?’ in B. De Jong et al. (eds.), The Rise of Public Security Interests in Corporate Mergers and Acquisitions (2022), at 63-85; N. Zamani, ‘The Rise of Geo-Economics: Saying A, Meaning B and Pursuing C?’, Op-Ed EU Law Live; R.D. Blackwill and J.M. Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (2016); M. Wesley, ‘Australia and the Rise of Geoeconomics’, 29 Centre of Gravity 1 (2016) and A. Roberts, H.C. Moraes & V. Ferguson, ‘Toward a Geoeconomics World Order in International Trade and Investment’, 22 Journal of International Economic Law 655 (2019). The war in Ukraine and the current energy crisis in many EU Member States is a prime example of this tendency. Therefore, if owing to outbound FDI the protection of vital goods and services is relocated to third countries, the EU might become economically, and thus also politically, dependent on those third countries. In its Covid-19 guidelines, the Commission warned thatthere could be an increased risk of attempts to acquire healthcare capacities (for example for the protection of medical or protective equipment) or related industries such as research establishments (for instance developing vaccines) via foreign direct investment.

According to the Commission, ‘[v]igilance is required to ensure that any such FDI does not have a harmful impact on the EU’s capacity to cover the health needs of its citizens’.30x European Commission, COVID-19 guidelines (26 March 2020), OJ C 99 I. It is thus necessary to screen outbound FDI to prevent the relocation of the production and development of vital products and services to third countries, as a consequence of which the EU will be placed in a position of dependency.

Third, it is important to be aware of the developments at the international level with regard to the screening of outbound FDI. The EU ranks, together with the United States, China, Japan and South Korea, among the leaders in innovation and technology. All these countries are (considering the) screening (of) outbound FDI. Thus, if the EU is not to lose ground, some form of screening of outbound FDI is necessary. This holds even more now that the NCCDA contains a provision on the basis of which the US Trade Representative can conduct multilateral engagement with the governments of countries that are allies of the United States to coordinate protocols and procedures for the screening of outbound FDI and establish information sharing regimes.31x Sec. 1011 NCCDA. It is thus likely that the United States will put some pressure on the EU and its Member States to also screen outbound FDI.

Finally, it can be argued that the already existing possibilities for the EU and its Member States are inadequate to address and mitigate the risks associated with outbound FDI. In accordance with established case law, FDI falls within the scope of the free movement of capital ex Article 63 TFEU.32x See for instance Case 174/04, Commission v. Italy, [2005] ECR I, Rec 27. The screening of outbound FDI is a restriction of the free movement of capital that needs to be justified. The justificatory grounds as laid down in the TFEU are, however, not suitable since the material and temporal scope of these grounds is (very) limited. Article 64(1) TFEU concerns the so-called grandfather clause. It allows Member States to maintain restrictions on the movement of capital with third countries if they existed prior to 31 December 1993. To invoke Article 64(1) TFEU, it is only required that the restrictions already existed before 31 December 1993. No additional conditions, such as the proportionality test, are imposed. Hence, the temporal dimension implies that the scope of Article 64(1) TFEU is limited to restrictions that already existed before 31 December 1993. Article 66 TFEU empowers the Council to apply safeguards in respect of third countries if the movement of capital from third countries causes or threatens to cause serious difficulties for the functioning of the economic and monetary union. The justification of Article 66 TFEU is thus economic in nature, and it follows from the wording of Article 66 TFEU that recourse to this justificatory ground is possible only in exceptional cases. Article 75 TFEU is of a political nature and allows the European Parliament and the Council to establish a framework for administrative measures concerning, inter alia, capital movements to prevent and combat terrorism and related activities. These measures include, inter alia, the freezing of assets.33x See for an extensive analysis of this ground S. Hindelang, The Free Movement of Capital and Foreign Direct Investment: The Scope of Protection in EU Law (2009), at 311-25.

Article 65(1) TFEU contains two justificatory grounds. Article 65(1)(a) TFEU is not suitable for the screening of outbound FDI since the material scope of this ground is limited to taxation. Article 65(1)(b) TFEU allows Member States to restrict the free movement of capital on the grounds of, inter alia, public policy and public security. The rationale behind these grounds is the recognition that, despite the integration process, Member States have structured their societies in different ways with different norms and values.34x T. Hosko, ‘Public Policy as an Exception to Free Movement within the Internal Market and the European Judicial Area: A Comparison’, 10 Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy 189, at 189-90 (2014). To give Member States room to accommodate their own interests within them, public order and public security are not defined in either primary or secondary EU law. Moreover, the Court has also been reluctant to define public order and security. The lack of clear definitions is not only a logical choice from the point of view of the rationale of these grounds but also the result of dogmatic incapacity: it is very difficult, if not impossible, to define these grounds precisely. Member States may invoke public policy and public security to pursue different interests that do not necessarily need to be consistent with each other. After all, the public policy and public security of one Member State is not the public policy and public security of another.

The absence of precise definitions does not mean, however, that Member States have carte blanche with respect to the application of these grounds. According to established case law of the Court, these grounds must be interpreted strictly and invokedonly if they are necessary for the protection of the interests which they are intended to guarantee and only in so far as those objectives cannot be attained by less restrictive measures.35x Case 54/99, Église de Scientology, [2000] ECR I, Rec 17-18.

Moreover, the mere existence of an interest falling under public policy and/or public security is, according to the Court, not sufficient to justify measures restricting the free movement of capital. Rather, the Court requires that a number of additional conditions must be met.36x Ibid. These conditions are as follows:

the invocation of these grounds must not lead to arbitrary discrimination or disguised restriction (Art. 65(3) TFEU);

there must be a genuine and sufficiently serious threat to a fundamental interest of society;

no purely economic objectives must be pursued;

the measures taken must be the least restrictive and, finally,

persons affected by the restrictive measures must have access to legal remedies.

Besides these strict conditions, the material scope of public policy and public security is limited and inadequate to address and mitigate the risks associated with outbound FDI. An in-depth analysis of these grounds is beyond the scope of this contribution.37x See for such a discussion: N. Zamani, ‘Screening Foreign Direct Investments on the Basis of Security and Public Order: Paving the Way for Protectionism?’ (forthcoming). However, it follows from the case law of the Court that reliance on the public policy exception is justified in the case of human dignity,38x Case 36/02 Omega Spielhallen [2004] ECR I, Rec 40. the fight against artificial constructions to circumvent legislation,39x Case 235/17, Commissie v. Hongarije, [2009] published in the electronic Reports of Cases, Rec 112. the promotion of social housing,40x Case 567/07, Servatius [2009] ECR I, Rec 28. the protection of minted coins41x Case 7/78, Regina [1978] ECR I, Rec 33. and the fight against money laundering.42x Case 190/17, Zheng [2018] published in the electronic Reports of Cases, Rec 38. Moreover, the Union legislature has indicated that public policy may also include the protection of minors and vulnerable adults and animal welfare.43x Recital 41 of Directive 2006/123/EG of the European Parliament and the Council, OJ L 376/27. The public security covers, according to the case law of the Court, hard-core (military) security issues, such as the protection of citizens and territory and the fight against organised crime44x Case 78/18, Commissie v. Hongarije [2020] not yet published, Rec 90. and terrorism.45x Case 482/17, Czech Republic v. Parliament and Council [2019] published in the electronic Reports of Cases, Rec 40. Furthermore, the public security exception can be invoked for the purpose of ensuring the provision of essential public services in the petroleum,46x Case 72/83, Campus Oil [1984] ECR I, Rec 33-4. energy (including the gas and electricity sectors)47x Case 543/08, Commission v. Portugal [2010] ECR I, Rec 84. and telecommunications sectors.48x Case 463/00, Commission v. Spain [2003] ECR I, Rec 71-2. Finally, the Court held that restrictive export measures related to dual-use goods, which are products and services that can be used for both civilian and military purposes, fall within the scope of the public security exception.49x Case 70/94, Werner [1995] ECR I, Rec 28.

-

4 The NCCDA Proposal

4.1 Background

The legislators and regulators of many states are so far focused mainly on the potentially detrimental effects of only inbound FDI, while outbound FDI has not received any particular attention. Consequently, outbound FDI falls outside the scope of almost all the FDI screening mechanisms that have been put in place in the last couple of years. Of the ten largest economies affiliated with the OECD, Japan and South Korea are so far the only countries that have a sort of screening mechanism for outbound FDI. Japan has a prior notification system. Investors and companies operating in the fishing, narcotics, arms and leather industries are required to report outbound FDI to the authorities.50x T. Hanemann et al., ‘An Outbound Investment Screening Regime for the United States?’, The US-China Investment Project Report (2022), at 18. South Korea has a more or less similar system. Pursuant to Article 11-2 first paragraph of the Act on Prevention of Divulgence and Protection of Industrial Technology (APDPIT),51x The APDPIT, www.elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=24351&lang=ENG.

an institution … [that] possesses national nuclear technology developed with government research and development grants, intends to proceed with foreign investment … [shall] notify the Minister of Knowledge Economy in advance.

Under Article 11-2 third paragraph APDPIT, the minister can then decide to prohibit a proposed investment.

In view of the Covid-19 crisis and the geopolitical rivalry with China,52x See with regard to this inter alia Roberts, Moraes & Ferguson, above n. 29. concerns have been voiced in the United States to also screen outbound FDI. At the National Security Commission on artificial intelligence global emerging technology summit, Jake Sullivan, the National Security Advisor, noted that[the US was] looking at the impact of outbound US investment flows that could circumvent the spirit of export controls or otherwise enhance the technological capacity of our competitors in ways that harm our national security.53x Remarks of Jake Sullivan at the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence Global Emerging Technology Summit (13 July 2021), www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/briefing-room/2021/07/13/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-at-the-national-security-commission-on-artificial-intelligence-global-emerging-technology-summit/.

Hence, it seems that the screening of outbound FDI is concerned primarily with those transactions that do not fall within the scope of the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA), introduced in 2018. Also, the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission recommended in its annual 2021 report to the Congress that the Congress should

consider legislation to create the authority to screen the offshoring of critical supply chains and production capabilities to the Peoples Republic of China to protect U.S. national and economic security interests…. This would include screening related outbound investment by U.S. entities.54x US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, ‘2021 Report to the Congress’ (November 2021), at 168, www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/2021_Annual_Report_to_Congress.pdf.

However, the approach of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission seems to be broader than national security issues only. It explicitly states that the purpose of the legislation should also be to ‘identify whether critical U.S. interests are being adversely affected, including the loss of domestic production capacity and capabilities’.55x Ibid. The reference to domestic production capacity and capabilities gives at least the impression that outbound FDI should be screened not only on national security grounds but also on economic grounds. Accordingly, some commentators have argued that the NCCDA proposal pursues two objectives: preventing US national security from being adversely affected by outbound FDI and protecting US jobs and factories and thus the US economy.56x See inter alia T. Smith, ‘Outbound Investment Screening Proposals Should Be Narrow and Targeted’, American Action Forum (6 October 2022), www.americanactionforum.org/insight/outbound-investment-screening-proposals-should-be-narrow-and-targeted/; J. Chaisse, ‘Is the US Going to Screen Outbound FDI?’, FDI Intelligence (14 October 2022), www.fdiintelligence.com/content/feature/is-the-us-going-to-screen-outbound-fdi-81497. If the NCCDA indeed also pursues economic objectives, or if other states interpret it in this way, then its adoption might provoke counter legislation that will lead to further protectionism and decline in FDI transactions.57x D. Plotinsky, C. Renner & K.M. Hilferty, ‘US National Security Review for Outbound FDI: Domestic and Global Impact’, Morgan Lewis (9 May 2022), www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2022/05/us-national-security-review-for-outbound-investment-domestic-and-global-impact. The US Chamber of Commerce expressed its concerns in this regard since the current NCCDA proposal would adopt a broad understanding of national security, thereby putting US companies at a competitive disadvantage.58x US Chamber of Commerce, ‘Coalition Letter on the National Critical Capabilities and Defense Act’ (23 June 2022), www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/220623_Coalition_NationalCriticalCapabilitiesDefenseAct_Congress_2022-06-24-125102_nlcb.pdf.

4.2 Scope

Pursuant to Sec. 1002(a) NCCDA, a Committee on National Critical Capabilities (the NCC Committee) is established that is charged with screening covered transactions. A covered transaction is defined as

any transaction by a United States business that shifts or relocates to a country of concern, or transfers to an entity of concern, the design, development, production, manufacture, fabrication, supply, servicing, testing, management, operation, investment, ownership, or any other essential elements involving one or more national critical capabilities … or could result in an unacceptable risk to a national critical capability.59x Sec. 1001(5)(A)(i)(I) and (I)) NCCDA.

The material scope of the NCCDA is thus quite broad. First of all, the definition of a covered transaction is not limited solely to investments, let alone FDI, but encompasses all sorts of transactions that shift, relocate or transfer any part of the production process of national critical capabilities.60x For the purpose of the present article, I will focus only on the screening of outbound FDI and will not discuss the screening of other forms of covered transactions. Second, the term ‘investment’ is employed, which is obviously a broader concept than FDI since it also includes portfolio investments. Finally, the NCCDA also contains a broadly construed anti-circumvention clause. Pursuant to Sec. 1001(5)(A)(ii) NCCDA, all transactions, transfers, agreements and arrangements that are designed or intended to circumvent the application of this act are also qualified as covered transactions.

From the definition of covered transaction, it follows that the NCC Committee can screen a transaction if (i) it is related to national critical capabilities or, while not directly relating to national critical capabilities, may lead to unacceptable risks to national critical capabilities in (ii) countries or entities of concern. Thus, before the NCC Committee screens a specific covered transaction, two cumulative conditions must be met. First, the specific covered transaction must involve or result in unacceptable risks to national critical capabilities. Second, the covered transaction must take place in countries or entities of concern.

With respect to the first condition, Sec. 1001(11)(A) NCCDA states that national critical capabilities should be understood as ‘systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that the inability to develop such systems and assets or the incapacity or destruction of such systems or assets would have a debilitating impact on national security or crisis preparedness’. Sec. 1001(11)(B) NCCDA contains an indicative list of national critical capabilities whereby a distinction is made between the production in sufficient quantities of certain articles such as medicines and personal protection equipment,61x Sec. 1001(11)(B)(i) NCCDA. supply chains62x Sec. 1001(11)(B)(ii-iv) NCCDA. and medical and other services critical to the maintenance of (critical) infrastructure (construction).63x Sec. 1001(11)(B)(v-viii) NCCDA. Besides this indicative list, Sec. 1007(b) NCCDA lists eleven industries that the NCC Committee should review to identify and recommend additional articles, supply chains and services to be included in the definition of national critical capabilities. Besides industries such as energy, defence, robotics, semiconductors and artificial intelligence, the list also includes the communication, transportation and water industries.

With respect to the second condition, guidance is provided by Sec. 1001(4) NCCDA. It defines countries of concern as (A) foreign adversaries and (B) non-market economy countries. A foreign adversary is, pursuant to Section 8(c)(2) of the Secure and Trusted Communications Network Act of 2019,64x The Secure and Trusted Communications Network Act of 2019, www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ124/PLAW-116publ124.pdf. a ‘foreign government or foreign nongovernment person engaged in a long-term pattern or serious instance of conduct significantly adverse to the national security of the United States or security and safety of the United States persons’. Foreign adversaries are thus countries that are, in short, hostile towards the United States and include China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela and Cuba.65x See the list of the Department of Commerce (DOC), www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-01-19/pdf/2021-01234.pdf. Countries that are defined as non-market economies concern Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, China, Georgia, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.66x See the list provided by the International Trade Administration, www.trade.gov/nme-countries-list. Entities of concern are all entities that have ties, direct or otherwise, with countries of concern.67x Sec. 1001(8) NCCDA.4.3 Procedure

Once a transaction can be qualified as a covered transaction by meeting the two conditions discussed previously, the company concerned must report the transaction to the NCC Committee.68x Sec. 1003(a) NCCDA. The NCC Committee has sixty days to screen the transaction. The NCC Committee has, however, also the competence to screen ex officio covered transactions that are not notified by the companies concerned.69x Sec. 1003(b)(2) NCCDA. Yet another possibility is that the NCC Committee shall screen covered transactions upon the request of the chairperson and the ranking member of one of the congressional committees jointly.70x Sec. 1003(b)(3) NCCDA. Here the NCC Committee has no discretion, as indicated by the word ‘shall’, in contrast to the other options, where the word ‘may’ is used.

Sec. 1005 NCCDA provides an indicative list of factors that the NCC Committee should take into account in assessing whether a specific covered transaction results in unacceptable risks to national critical capabilities. These factors include United States’ long-term strategic interests in the economy, national security and crisis preparedness, the country and foreign party specifics and the impact on domestic industry.71x Sec. 1005(1-4) NCCDA. If the NCC Committee concludes that a specific FDI transaction results in unacceptable risks to national critical capabilities, it makes recommendations to the president and the Congress to address or mitigate the risks.72x Sec. 1003(a)(B)(i-ii) NCCDA.

After receiving the recommendations of the NCC Committee, the president can take any action for such a time as he deems appropriate to address or mitigate the unacceptable risks to the national critical capabilities. He can, inter alia, suspend or even prohibit the transaction.73x Sec. 1004(a) NCCDA. Within 15 days, the president has to announce the decision whether or not he will take action.74x Sec. 1004(b) NCCDA. The president can only suspend or prohibit a transaction if, according to him, there is credible evidence that the transaction possesses unacceptable risks to national critical capabilities that cannot be addressed adequately by other means.75x Sec. 1004(d)(1-2) NCCDA. In making such an assessment, the president should take into account, inter alia, the factors provided by Sec. 1005.76x Sec. 1004(e) NCCDA.4.4 Screening Grounds

The decision to screen, and eventually to suspend or even prohibit, a specific FDI transaction depends on whether the transaction concerned would have a debilitating impact on national security or crisis preparedness. The screening grounds are thus national security and crisis preparedness.77x Sec. 1001(11) NCCDA. For a definition of national security, a reference is made to Sec. 721(a) and Sec. 702 of the Defense Production Act of 1950,78x The Defense Production Act of 1950, www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-03/Defense_Production_Act_2018.pdf. according to which national security means issues related to homeland security, including its application to critical infrastructure and national defence.79x Sec. 1001(12)(A-B) NCCDA. Homeland security is related to the efforts to prevent and minimise damages resulting from terrorist attacks.80x Sec. 702(11) of the Defense Production Act of 1950. Moreover, national security also includes, quite curiously, agricultural security and natural resources security.81x Sec. 1001(12)(C) NCCDA. Crisis preparedness refers to the preparedness for public health emergencies and other major disasters.82x Sec. 1001(6) NCCDA.

4.5 Further Regulations and Multilateral Engagement

The NCC Committee is required to prescribe further regulations to carry out the NCCDA.83x Sec. 1009(a) NCCDA. The regulations should prescribe the civil penalties for violating the provisions of the NCCDA.84x Sec. 1009(b)(1) NCCDA. Furthermore, the NCC Committee is obliged to provide specific examples of transactions that can be qualified as covered transactions.85x Sec. 1009(b)(2)(A) NCCDA. Finally, the NCC Committee should also provide examples of articles, supply chains and services that it considers to be national critical capabilities.86x Sec. 1009(b)(2)(B) NCCDA.

The NCCDA also aims to set up cooperation mechanisms with its allies. Pursuant to Sec. 1011(1) NCCDA, the US Trade Representative should conduct multilateral engagement with allies in order to coordinate protocols and procedures with regard to covered transactions. Once such coordinated protocols and procedures are adopted, the US Trade Representative should engage with the allies of the United States to establish regimes for information sharing.87x Sec. 1011(2) NCCDA. -

5 Towards an EU Outbound FDI Screening Mechanism

5.1 Preliminary Observations

Before drawing lessons from the NCCDA proposal, it is important to note that the EU differs significantly from the United States in certain respects. One of these concerns the fact that the US is a unitary state, while the EU is a Union composed of twenty-seven nation states, whose interests do not necessarily need to be aligned. The process towards the adoption of Regulation 2019/452 is illustrative in this regard. During the European Council Summit in June 2017, some Nordic, Central and Eastern European Member States were quite reluctant to have inbound FDI screened. The Polish prime minister, for instance, stated that ‘Poland will firmly oppose protectionist measures in the European Union’.88x Politico, ‘European Council: as it happened’ (22 June 2017), www.politico.eu/article/european-council-live-blog-2/. Accordingly, the experiences from the United States cannot be translated directly to the EU and its Member States. Nevertheless, the NCCDA proposal is insightful with regard to the question of how a future EU outbound FDI screening mechanism can be drafted.

5.2 Legal Basis: Article 64(3) TFEU

As is clear from the foregoing, it is necessary that the EU and its Member States establish an EU outbound FDI screening mechanism. The question that immediately arises concerns the legal basis under which the future EU outbound FDI screening mechanism can be adopted. At first sight, Article 207(2) TFEU seems to be in this regard the most obvious option, since FDI is part of the Common Commercial Policy (CCP),89x Pursuant to Art. 207(1) TFEU, FDI are part of the CCP. an area where the EU has exclusive competence.90x Art. 3(1)(e) TFEU. Under this legal basis, the European Parliament and the Council, acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure and by means of only regulations, can adopt measures defining the framework for the implementation of the CCP. Article 207(2) also served as the legal basis for Regulation 2019/452.91x See the first point of the preamble of Regulation 2019/452. See also point 2 of the Explanatory Memorandum of Regulation 2019/452 (COM(2017)487 final). Accordingly, one can argue that Article 207(2) TFEU would also be the correct legal basis for setting up an outbound FDI screening mechanism. On second thoughts, however, things are somewhat more nuanced, and, in my view, Article 64(2) or (3) TFEU would be a more appropriate legal basis. Article 64(2) or (3) TFEU can serve as legal basis because FDI are, pursuant to point 1 of the Nomenclature to Directive 88/361/EC, examples of capital movements in the sense of Article 63(1) TFEU.92x Zie bijvoorbeeld HvJ EU 2 juni 2005, C-174/04, ECLI:EU:C:2005:250 (Commissie/Italië), r.o. 27. Accordingly, it is possible to use the internal market legal basis of Article 64(2) or (3) TFEU. In order to build the argument that Article 64(2) or (3) TFEU is a more suitable legal basis than Article 207(2) TFEU, the analysis of Cremona93x M. Cremona, ‘Regulating FDI in the EU Legal Framework’, in J.H.J. Bourgeois (ed.), EU Framework for Foreign Direct Investment Control (2020), at 31-55. in the context of Regulation 2019/452 is insightful.

Cremona distinguishes four different types of regulatory (inward) FDI instruments.94x Ibid., at 40-50. The first concerns regulatory instruments that do not create new standards but that simply refer to already existing obligations in international agreements. The second type of regulatory instruments extend already existing EU internal market law standards to third countries. The third type, under which Regulation 2019/452 also falls, according to Cremona,95x Ibid., at 43. is concerned with the setting up of legal frameworks within whose boundaries Member States can exercise their powers. This type is thus not about harmonising or imposing new obligations but rather about creating a legal framework. For these three types of regulatory instruments, Article 207(2) TFEU is, in principle, the appropriate legal basis. The last form of regulatory instruments is about harmonising certain standards or creating new regulatory controls. The choice of the legal basis (i.e. Article 207(2) or 64(2)/(3) TFEU) here is dependent on the primary purpose of the legislation. If the legislation is aimed primarily at the internal market and non-EU companies are affected only incidentally by it, then Article 64(2) or (3) is the appropriate legal basis.

Considering these four types, it is clear that establishing an EU outbound FDI screening mechanism clearly does not fall under the first two types since there are no international or EU internal market law standards yet with regard to the screening of outbound FDI. Whether the third or fourth type is applicable is dependent on the level of harmonisation and whether new regulatory controls are created. In my opinion, a certain level or harmonisation and creation of new regulatory controls is necessary for the effectiveness of the mechanism. Hence, the fourth is applicable. Given the fact that a future EU outbound FDI screening mechanism is aimed primarily at the internal market and that non-EU companies are affected only incidentally, Article 64(2) or (3) TFEU would be the most appropriate legal basis. Whether the second or third paragraph of Article 64 TFEU should be taken as the legal basis depends on whether the screening of outbound FDI constitutes a step backwards in EU law with regard to the liberalisation of the free movement of capital to third countries. It is reasonable to argue that screening outbound FDI indeed entails a step backwards in the liberalisation of the capital movements to third countries.96x See for a similar argument with regard to inbound FDI: Cremona, ‘Regulating FDI in the EU Legal Framework’, in J.H.J. Bourgeois (ed.), EU Framework for Foreign Direct Investment Control (2020), at 37-8. After all, outbound FDI, and thus the free movement of capital, is restricted because EU companies can no longer invest in certain third countries without impediments. Hence, Article 64(3) TFEU would be the appropriate legal basis for a future EU outbound FDI screening mechanism. Article 64(3) TFEU is an internal market legal basis. Pursuant to Article 4(2)(a) TFEU, the EU shares competence with the Member States in the internal market area. Accordingly, in order to successfully set up an EU outbound screening mechanism, cooperation between the EU and its Member States is necessary. This might prove to be rather difficult, considering the experience with the adoption of Regulation 2019/452. There are indeed Member States that are more in favour of screening FDI than others. Nevertheless, an EU-wide outbound FDI screening mechanism is a necessity, and therefore the EU and its Member States should consider it.5.3 Ex ante Screening

Pursuant to Sec. 1003(a) NCCDA, parties to a covered transaction are obliged to submit a written notification of the transaction to the NCC Committee. After receiving the written notification, the NCC Committee will review the covered transaction. This effectively amounts to ex ante screening. For a future EU outbound screening mechanism, ex ante screening with a notification obligation is preferable to ex post screening, where a completed transaction is examined afterwards. Regulation 2019/452 has adopted the approach of ex post screening. From the perspective of the authorities in charge of screening, the advantage of ex ante screening with a reporting requirement is that they do not need to spend time and resources on identifying outbound FDI eligible for screening. For the parties, ex ante screening contributes to legal certainty as parties know in advance where they stand and do not run the risk of a reversal of an investment already made with all its consequences. Moreover, it also prevents irreversible consequences from materialising.

5.4 Ex officio Screening and a Cooperation Mechanism

A feature of the NCCDA is that it combines a notification obligation for the parties97x Sec. 1003(a) NCCDA. with the competence for the NCC Committee to, either ex officio or at the request of the chairperson and a ranking member of a congressional committee, screen covered transactions.98x Sec. 1003(b)(2) and (3) NCCDA. So in cases where the parties fail the notification obligation for whatever reason, the NCC Committee can still review the transaction. Combining a notification obligation with ex officio competences of the competent authorities is a useful approach since it ensures that all FDI transactions can be screened.

While the NCCDA proposal allows the chairperson and a ranking member of a congressional committee to request the screening of a covered transaction, in the context of the EU this, obviously, should be modified. More concretely, it would be desirable to allow other Member States and the Commission to request the screening of a particular FDI transaction. Such an approach would mirror the cooperation mechanism of Regulation 2019/452. Pursuant to Article 6(1) Regulation 2019/452, Member States have to notify the Commission and other Member States of FDI transactions in their territory that are undergoing screening by providing information such as the ownership structure of the foreign investor and the approximate value of the transaction.99x Art. 9(2) Regulation 2019/452 mentions the information that has to be provided by a Member State that is screening a particular FDI. The purpose of this notification obligation is to enable the other Member States and the Commission to issue comments and opinions, respectively, with regard to the FDI transaction that is undergoing screening.100x Art. 6(2) and (3) Regulation 2019/452. Even though the final screening decision will be taken by the Member State that is screening the FDI transaction,101x See in this regard for instance Recitals 17 and 19 and Art. 6(9) Regulation 2019/452. due consideration must be given to the comments and opinions received.102x Art. 6(9) Regulation 2019/452. Article 7 Regulation 2019/452 contains more or less the same procedure, but then for FDI that is not undergoing screening in a Member State. The reason behind the cooperation mechanism is to address the cross-border effects of FDI. An argument can be made that a similar approach should also be adopted with regard to the screening of outbound FDI since these FDI transactions can also have cross-border effects.5.5 Scope: Concentrating on FDI in Countries of Concern in a Limited Number of Sectors

The NCCDA contains a couple of interesting aspects with regard to the scope, which provide valuable lessons for a future EU outbound screening mechanism. First of all, the material scope of the NCCDA is quite broad since it employs the term ‘covered transaction’, which includes both portfolio investments and FDI as well as other transactions that shift, relocate or transfer (parts of) the production process of national critical capabilities. For a future EU outbound screening mechanism, it is desirable to focus solely on FDI rather than on the broader notion of covered transaction. If every investment in a third country, no matter how small, were subject to screening, that would lead to an enormous workload for the authorities. Moreover, one can also question what the added value would be of screening every investment and thus also portfolio investments. Portfolio investments are made for purely financial gains, without any intention to exercise influence over the management and/or control of a company.103x See for instance: Case 282/04, Commission v. Netherlands, [2006], Rec 19. After all, if a Dutch company buys, for instance, 1% of the shares in a Chinese company, then it may be questioned to what extent this transaction might lead to undesirable knowledge transfer or put the Netherlands (or the EU) in an economically, and thus also politically, dependent position. Moreover, screening every investment would unnecessarily and disproportionately hamper investments and thus economic growth.

Yet another interesting aspect of the NCCDA concerns the fact that its scope is limited to outbound FDI in countries and entities of concern. Limiting the scope of a future EU outbound screening mechanism to high-risk countries and entities has a number of advantages. First of all, it contributes to legal certainty. Parties intending to invest in high-risk countries and entities know in advance that the transaction should be notified and screened. Conversely, parties investing in non-high-risk countries and entities do not need to notify the transaction and go through the screening procedure. Secondly, limiting the scope of the screening mechanism to high-risk countries and entities prevents the unnecessary and disproportionate restriction of outbound FDI, and thus also economic growth. If all outbound FDI were subject to screening, then quite conceivably certain parties would refrain from investing abroad because of the time, money and effort that it takes to screen. In its first annual report on Regulation 2019/452, the Commission noted that 7% of FDI transactions in the formal screening phase were abandoned by the parties for unknown reasons.104x European Commission, First annual report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union (23 November 2021), COM(2021)714 final, at 11. Thirdly, the authorities’ workload is reduced because they are in charge of screening outbound FDI only in high-risk countries and entities. Finally, an argument can be made that the authorities charged with the screening of outbound FDI will develop a certain level of expertise because they are focused on a limited number of countries and entities.

A question that arises is which countries (and entities) should be considered as being of high risk. At the EU level, the Commission adopted, on 7 January 2022, a new delegated regulation105x Commission Delegated Regulation 2022/229, OJ L 39. wherein it composed a list of high-risk third countries in the context of anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism.106x Directive 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council, OJ L 141. These countries107x See Art. 3 of Delegated Regulation 2022/229. There are, in total, 23 countries on the list, such as Barbados, Cayman Islands, Jordan, Syria and Uganda. are classified as high-risk because they pose significant threats to the financial system of the EU. This list of countries is, however, not useful for the purpose of screening outbound FDI, first of all, because EU companies have not (significantly) invested in these countries. Secondly, and more importantly, countries that are considered to be high-risk destinations for outbound FDI are not on this list. China is, as explained earlier, such a country. Charles Michel, president of the European Council, stated, for instance, in a press release after the 22nd EU-China Summit, ‘that we have to recognize that we do not share the same values, political systems or approach to multilateralism’.108x Press release by President Michel and President Von der Leyen on EU-China Summit: Defending EU interests and values in a complex and vital partnership (22 juni 2020), www.consilium.europa.eu/nl/press/press-releases/2020/06/22/eu-china-summit-defending-eu-interests-and-values-in-a-complex-and-vital-partnership/. It is thus necessary that a separate list of high-risk countries is composed specifically in the context of outbound FDI. For the composition of this list, inspiration can be drawn from the list to which the NCCDA refers. As stated earlier, countries of concern are both foreign adversaries (China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela and Cuba)109x See the list of the Department of Commerce (DOC), www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-01-19/pdf/2021-01234.pdf. and non-market economies (the former Soviet Republics with the exception of Russia plus China and Vietnam).110x See the list provided by the International Trade Administration, www.trade.gov/nme-countries-list. The list of foreign adversaries will suffice for the time being; also because the number of outbound EU FDI in the former Soviet Republics will probably be not high.

It is important to note that by concentrating on the screening of outbound FDI in specific countries, the EU does not violate its international obligations. The main international obligations of the EU and its Member States in the area of FDI are contained in the GATS and in trade and investment treaties concluded with (a group of) countries, such as the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), with Canada and the Economic Partnership Agreement with Japan (EU-Japan Agreement). In the context of the screening of FDI, the market access rights provisions are relevant.111x See, for instance, Art. XVI GATS, Art. 8.4 CETA and Art. 8.7 EU-Japan Agreement. By screening, and eventually prohibiting FDI, access to the market is restricted for an investor. However, the screening of outbound FDI is not at odds with the market access obligation. The provisions relating to market access rights are intended to ensure market access for foreign investors. Market access rights are thus meant to prevent countries from denying foreign investors access to their national market. It is thus the screening of inbound, rather than outbound FDI, that might violate market access provisions. If the Netherlands screens, and eventually blocks the acquisition of a Dutch company by a Chinese investor, then that might entail a violation of the market access rights obligation. The reverse case, where the Netherlands screens and eventually prohibits the acquisition of a Chinese company by a Dutch company, is not true. Therefore, the provisions regarding market access rights are not applicable in the context of the screening of outbound FDI.

The scope of a future EU outbound screening mechanism should be further limited by adopting a sectoral approach. In contrast to the NCCDA (and Regulation 2019/452), however, the number of sectors wherein FDI transactions are subject to screening should be limited. The focus should be mainly on the defence, energy and health sectors. The communication, transportation or water sector, for instance, should not be included. The reason why the numbers of sectors wherein outbound FDI is subject to screening should be limited is threefold. First of all, one has to keep in mind that the primary objective of screening outbound FDI is to prevent the transfer of knowledge as a consequence of which the EU and its Member States become economically and, by definition, politically dependent. However, it is unreasonable and also undesirable to pursue full economic independence; unreasonable because the world economies are much too interconnected, undesirable because the whole raison d’être behind the liberalisation of trade and investments would vanish. Trade and investments are liberalised because of comparative advantages, and pursuing full economic independence is in direct contrast to that. Secondly, it may be questioned to what extent outbound FDI, for instance in the communications or water sectors, might lead to political dependency. Finally, screening transactions in too many sectors will unnecessarily and disproportionally hamper FDI.

In order to prevent circumvention, an anti-circumvention clause is necessary. The anti-circumvention clause must be broad enough to cover all the aspects of outbound FDI. Inspiration can be drawn in this regard from Sec. 1001(5)(A)(ii) NCCDA. -

6 Conclusion

After decades of having a free business environment, the world seems to be moving towards protectionism as liberalisation of FDI is increasingly being questioned. This is evidenced, inter alia, by the fact that more and more countries are tightening their existing mechanism for screening FDI and creating new ones. These screening mechanisms are meant to address and mitigate the risks associated with inbound FDI. Legislators and regulators are so far not paying any particular attention to the potentially detrimental effects of outbound FDI. The situation might change in the United States, however, where the bipartisan NCCDA proposal aims to establish a new regime for the screening of, inter alia, outbound FDI.

Considering (the legislative background of) the NCCDA proposal and the recent developments, wherein investment policies are increasingly used as tools to pursue strategic and geopolitical interests, it is necessary that the EU and its Member States also screen outbound FDI in order to prevent the undesirable transfer of sensitive knowledge and the relocation of the production of vital goods and services to third countries. In setting up a future EU outbound screening mechanism, inspiration can be drawn from the NCCDA proposal with regard to procedure, scope and screening grounds. More specifically, this means that the future EU outbound FDI screening mechanism must, first of all, combine ex ante and ex officio screening with a notification obligation for the parties to the transaction. Secondly, in order to address the cross-border effects of outbound FDI, it is necessary to have some kind of cooperation mechanism. Thirdly, the scope of a future EU outbound FDI screening mechanism must be limited only to FDI transactions in specific high-risk countries in a limited number of sectors. - * The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for providing valuable feedback and comments. This contribution is part of and related to a broader research interest of the author with regard to the interaction between geopolitics, geoeconomics and international and European economic law. More specifically, the present contribution builds on and is related to a forthcoming article (‘Screenen van uitgaande directe buitenlandse investeringen in een geo-economische wereldorde: wenselijk, noodzakelijk en mogelijk’) in SEW, Tijdschrift voor Europees en Economisch Recht.

-

1 Executive Order 11858, 40 FR 20263 (7 May 1975), www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/11858.html.

-

2 The National Critical Capabilities Act is accessible via Text S.1854, 117th Congress (2021-2022): National Critical Capabilities Defense Act of 2021, Congress.gov, Library of Congress, www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6329/text.

-

3 L.E. Trakman and N.W. Ranieri, ‘Foreign Direct Investment: An Overview’, in L.E. Trakman and N.W. Ranieri (eds.), Regionalism in International Investment Law (2013) 1, at 1.

-

4 Y.S. Lee, ‘Foreign Direct Investment and Regional Trade Liberalization: A Viable Answer for Economic Development?’ 39 Journal of World Trade 701, at 702 (2005). See for the history of FDI: Trakman and Ranieri, above n. 3, at 15-26.

-

5 Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council 2019/452, OJ L 791/1.

-

6 K.C. Cai, The Politics of Economic Regionalism. Explaining Regional Economic Integration in East Asia (2010), at 57-67. See with regard to the globalisation of the economic order: D. Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of World Economy (2011).

-

7 P. Van Den Bossche, The Law and Policy of the World Trade Organization. Text, Cases and Materials (2005), at 3.

-

8 Ibid., at 36.

-

9 The figure is taken from the website of the World Bank, www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?end=2020&start=1970&view=chart. See also: UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2021: Investing in sustainable recovery (2021), www.unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf#page=20; OECD, FDI in figures: April 2022, www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/FDI-in-Figures-April-2022.pdf.

-

10 European Commission, Towards a comprehensive European international investment policy (7 July 2010), COM(2010)343 final, at 3.

-

11 Ibid.

-

12 From 1970 until 2020, there were a couple of significant drops in FDI transactions. The first one was in 2003, which can be attributed to the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan and the subsequent war on terrorism. The second significant drop was in 2009, which was the consequence of the 2008 financial crises. In 2014, FDI transactions again fell significantly as a consequence of the global 2012/2013 financial crisis.

-

13 See for instance J. Wübbeke et al., ‘Made in China 2025: The Making of High-tech Superpower and Consequences for Industrial Countries’ (2016), at 52, www.merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Made%20in%20China%202025.pdf.

-

14 Letter of German, French and Italian governments to Commissioner Malmström (February 2017), www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/S-T/schreiben-de-fr-it-an-malmstroem.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5.

-

15 Ibid.

-

16 European Commission, Reflection paper on harnessing globalization (10 May 2017), COM(2017)240 final, at 18.

-

17 See inter alia: P. Corcoran, ‘Investing in Security: CFIUS and China after FIRRMA’, 52 New York University Journal of International Law and Politics (2019), at 7-14 and P. Rose, ‘FIRRMA and National Insecurity’, Ohio State Public Law Working Paper 2018:452, at 8-11.

-

18 OECD, Research Note on Current and Emerging Trends: Acquisition- and Ownership- Related Policies to Safeguard Essential Security Interests. New Policies to Manage New Threats (12 March 2019), at 4.

-

19 See inter alia: W.E. Veiligheid, Tussen naïviteit en paranoia: Nationale veiligheidsbelangen bij buitenlandse overnames en investeringen in vitale sectoren (2014); Kamerstukken II 2015/16, 30 821, nr. 27, at 2 and C.D.J. Bulten, B.J. de Jong & E.J. Breuking, Vitale vennootschappen in veilige handen (2017), at 142.

-

20 European Commission, EU-China A strategic outlook’ (12 March 2019), JOIN(2019)5 final, at 6.

-

21 The EU-China Joint Ventures Radar of Datenna, www.datenna.com/china-eu-joint-venture-radar. Datenna has also created an US-China Joint Ventures Rader, www.datenna.com/us-china-joint-venture-radar.

-

22 European Commission (March 2019), above n. 20.

-

23 D. Kwoken en Sam Goodman, ‘Chinese Communist Cells in Western Firms? Xi Jinping Has Pressed for Measures Giving Party Apparatchiks More Power over Foreign Companies’, Wallstreet Journal (11 July 2022), www.wsj.com/articles/communist-cells-in-western-firms-business-investment-returns-xi-jinping-11657552354. See also: J. Doyon, ‘Influence without Ownership: The Chinese Communist Party Targets the Private Sector’, Institut Montaigne (23 January 2021), www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/influence-without-ownership-chinese-communist-party-targets-private-sector.

-

24 Regulation (EU) 2021/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council of May 2021, setting up a Union regime for the export, brokering, technical assistance, transit and transfer of dual-use items, OJ L 206/I.

-

25 The Court employs the term dual-use goods while Regulation 2021/821 uses the term dual-use items. For convenience, the term ‘dual-use items’ will henceforth be used, thereby assuming that it is a synonym for dual-use goods.

-

26 The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for raising this question.

-

28 www.centric.eu/en/news/centric-helps-dnb-increase-it-flexibility-and-performance/.

-

29 See inter alia: N. Zamani, ‘The Economization and Politization of International Economic Law: Toward a Geo-Economic Legal Order?’ in B. De Jong et al. (eds.), The Rise of Public Security Interests in Corporate Mergers and Acquisitions (2022), at 63-85; N. Zamani, ‘The Rise of Geo-Economics: Saying A, Meaning B and Pursuing C?’, Op-Ed EU Law Live; R.D. Blackwill and J.M. Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (2016); M. Wesley, ‘Australia and the Rise of Geoeconomics’, 29 Centre of Gravity 1 (2016) and A. Roberts, H.C. Moraes & V. Ferguson, ‘Toward a Geoeconomics World Order in International Trade and Investment’, 22 Journal of International Economic Law 655 (2019).

-

30 European Commission, COVID-19 guidelines (26 March 2020), OJ C 99 I.

-

31 Sec. 1011 NCCDA.

-

32 See for instance Case 174/04, Commission v. Italy, [2005] ECR I, Rec 27.

-

33 See for an extensive analysis of this ground S. Hindelang, The Free Movement of Capital and Foreign Direct Investment: The Scope of Protection in EU Law (2009), at 311-25.

-

34 T. Hosko, ‘Public Policy as an Exception to Free Movement within the Internal Market and the European Judicial Area: A Comparison’, 10 Croatian Yearbook of European Law and Policy 189, at 189-90 (2014).

-

35 Case 54/99, Église de Scientology, [2000] ECR I, Rec 17-18.

-

36 Ibid.

-

37 See for such a discussion: N. Zamani, ‘Screening Foreign Direct Investments on the Basis of Security and Public Order: Paving the Way for Protectionism?’ (forthcoming).

-

38 Case 36/02 Omega Spielhallen [2004] ECR I, Rec 40.

-

39 Case 235/17, Commissie v. Hongarije, [2009] published in the electronic Reports of Cases, Rec 112.

-

40 Case 567/07, Servatius [2009] ECR I, Rec 28.

-

41 Case 7/78, Regina [1978] ECR I, Rec 33.

-

42 Case 190/17, Zheng [2018] published in the electronic Reports of Cases, Rec 38.

-

43 Recital 41 of Directive 2006/123/EG of the European Parliament and the Council, OJ L 376/27.

-

44 Case 78/18, Commissie v. Hongarije [2020] not yet published, Rec 90.

-

45 Case 482/17, Czech Republic v. Parliament and Council [2019] published in the electronic Reports of Cases, Rec 40.

-

46 Case 72/83, Campus Oil [1984] ECR I, Rec 33-4.

-

47 Case 543/08, Commission v. Portugal [2010] ECR I, Rec 84.

-

48 Case 463/00, Commission v. Spain [2003] ECR I, Rec 71-2.

-

49 Case 70/94, Werner [1995] ECR I, Rec 28.

-

50 T. Hanemann et al., ‘An Outbound Investment Screening Regime for the United States?’, The US-China Investment Project Report (2022), at 18.

-

51 The APDPIT, www.elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=24351&lang=ENG.

-

52 See with regard to this inter alia Roberts, Moraes & Ferguson, above n. 29.

-

53 Remarks of Jake Sullivan at the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence Global Emerging Technology Summit (13 July 2021), www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/briefing-room/2021/07/13/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-at-the-national-security-commission-on-artificial-intelligence-global-emerging-technology-summit/.

-

54 US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, ‘2021 Report to the Congress’ (November 2021), at 168, www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/2021_Annual_Report_to_Congress.pdf.

-

55 Ibid.

-

56 See inter alia T. Smith, ‘Outbound Investment Screening Proposals Should Be Narrow and Targeted’, American Action Forum (6 October 2022), www.americanactionforum.org/insight/outbound-investment-screening-proposals-should-be-narrow-and-targeted/; J. Chaisse, ‘Is the US Going to Screen Outbound FDI?’, FDI Intelligence (14 October 2022), www.fdiintelligence.com/content/feature/is-the-us-going-to-screen-outbound-fdi-81497.

-

57 D. Plotinsky, C. Renner & K.M. Hilferty, ‘US National Security Review for Outbound FDI: Domestic and Global Impact’, Morgan Lewis (9 May 2022), www.morganlewis.com/pubs/2022/05/us-national-security-review-for-outbound-investment-domestic-and-global-impact.

-

58 US Chamber of Commerce, ‘Coalition Letter on the National Critical Capabilities and Defense Act’ (23 June 2022), www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/220623_Coalition_NationalCriticalCapabilitiesDefenseAct_Congress_2022-06-24-125102_nlcb.pdf.

-

59 Sec. 1001(5)(A)(i)(I) and (I)) NCCDA.

-

60 For the purpose of the present article, I will focus only on the screening of outbound FDI and will not discuss the screening of other forms of covered transactions.

-

61 Sec. 1001(11)(B)(i) NCCDA.

-

62 Sec. 1001(11)(B)(ii-iv) NCCDA.

-

63 Sec. 1001(11)(B)(v-viii) NCCDA.

-

64 The Secure and Trusted Communications Network Act of 2019, www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ124/PLAW-116publ124.pdf.

-

65 See the list of the Department of Commerce (DOC), www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-01-19/pdf/2021-01234.pdf.

-

66 See the list provided by the International Trade Administration, www.trade.gov/nme-countries-list.

-

67 Sec. 1001(8) NCCDA.

-

68 Sec. 1003(a) NCCDA.

-

69 Sec. 1003(b)(2) NCCDA.

-

70 Sec. 1003(b)(3) NCCDA.

-

71 Sec. 1005(1-4) NCCDA.

-

72 Sec. 1003(a)(B)(i-ii) NCCDA.

-

73 Sec. 1004(a) NCCDA.

-

74 Sec. 1004(b) NCCDA.

-

75 Sec. 1004(d)(1-2) NCCDA.

-

76 Sec. 1004(e) NCCDA.

-

77 Sec. 1001(11) NCCDA.

-

78 The Defense Production Act of 1950, www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-03/Defense_Production_Act_2018.pdf.

-

79 Sec. 1001(12)(A-B) NCCDA.

-

80 Sec. 702(11) of the Defense Production Act of 1950.

-

81 Sec. 1001(12)(C) NCCDA.

-

82 Sec. 1001(6) NCCDA.

-

83 Sec. 1009(a) NCCDA.

-

84 Sec. 1009(b)(1) NCCDA.

-

85 Sec. 1009(b)(2)(A) NCCDA.

-

86 Sec. 1009(b)(2)(B) NCCDA.

-

87 Sec. 1011(2) NCCDA.

-

88 Politico, ‘European Council: as it happened’ (22 June 2017), www.politico.eu/article/european-council-live-blog-2/.

-

89 Pursuant to Art. 207(1) TFEU, FDI are part of the CCP.

-

90 Art. 3(1)(e) TFEU.

-

91 See the first point of the preamble of Regulation 2019/452. See also point 2 of the Explanatory Memorandum of Regulation 2019/452 (COM(2017)487 final).

-

92 Zie bijvoorbeeld HvJ EU 2 juni 2005, C-174/04, ECLI:EU:C:2005:250 (Commissie/Italië), r.o. 27.

-

93 M. Cremona, ‘Regulating FDI in the EU Legal Framework’, in J.H.J. Bourgeois (ed.), EU Framework for Foreign Direct Investment Control (2020), at 31-55.

-

94 Ibid., at 40-50.

-

95 Ibid., at 43.

-

96 See for a similar argument with regard to inbound FDI: Cremona, ‘Regulating FDI in the EU Legal Framework’, in J.H.J. Bourgeois (ed.), EU Framework for Foreign Direct Investment Control (2020), at 37-8.

-

97 Sec. 1003(a) NCCDA.

-

98 Sec. 1003(b)(2) and (3) NCCDA.

-

99 Art. 9(2) Regulation 2019/452 mentions the information that has to be provided by a Member State that is screening a particular FDI.

-

100 Art. 6(2) and (3) Regulation 2019/452.

-